Disco Medley

Elena Ketelsen González

- Text

As a young child visiting their great-grandparents’ ranch in Texas’s Rio Grande Valley, Leslie Martinez encountered a fleck of paint that would forever shape the way they looked at the world—and themselves. At the back-porch entrance, a rogue brushstroke graced a weathered brick. To Martinez, the wayward mark resembled a horse in motion, a precious symbol of freedom found amidst the harsh desert terrain. Over thirty years later, this vestige would cinch the first painting of Martinez’s solo exhibition at MoMA PS1, The Fault of Formation.

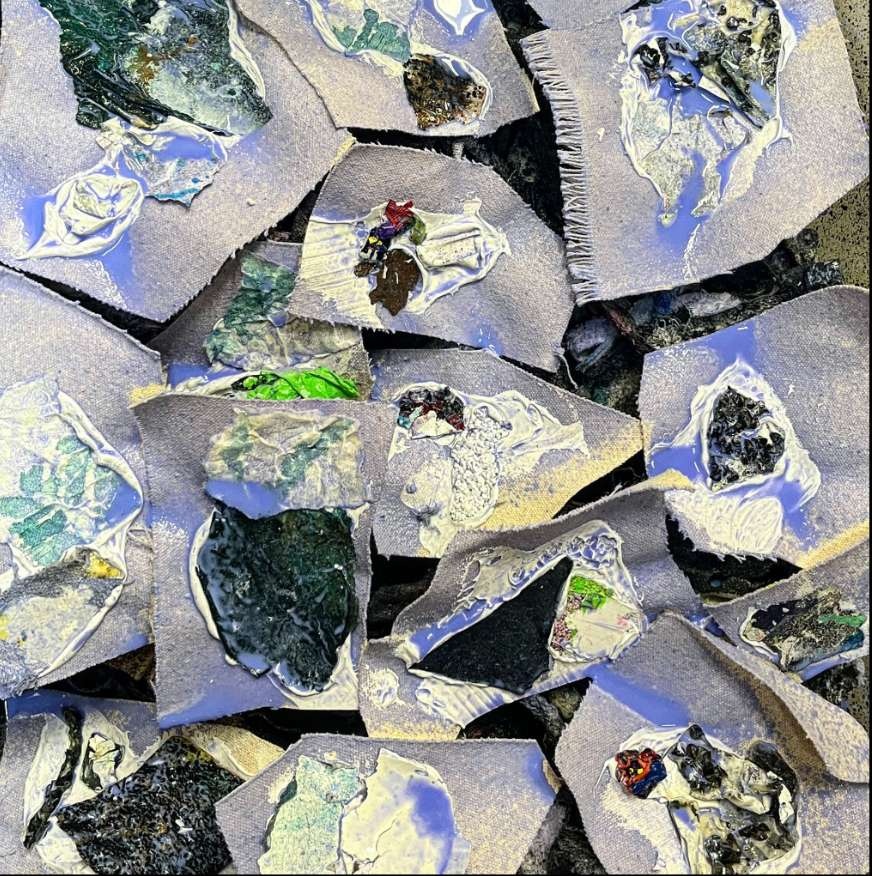

Plastic film stuffing, paper fragments, mophead fibers, and glass beads bisect the canvas of Out of the Gap Where Darkness Echos, Mustangs Took Off Running (2023) to form a horizon line. A blue opening anchors the painting at the top, under which strobing blisters of white paint drip down the canvas. Martinez considers this work an homage to a “failed painting” they made before leaving New York City, where they lived and worked for fifteen years before returning to Texas in 2019. Much like the equine mark, this painting presented an opportunity to see anew, to queer linear notions of time and desirability by returning to the fleeting past in order to drive towards the future. 1 In this manner, Martinez recalls theorist Jack Halberstam’s assertion that “in true camp fashion, the queer artist works with rather than against failure and inhabits the darkness.” 2

As a young child visiting their great-grandparents’ ranch in Texas’s Rio Grande Valley, Leslie Martinez encountered a fleck of paint that would forever shape the way they looked at the world—and themselves. At the back-porch entrance, a rogue brushstroke graced a weathered brick. To Martinez, the wayward mark resembled a horse in motion, a precious symbol of freedom found amidst the harsh desert terrain. Over thirty years later, this vestige would cinch the first painting of Martinez’s solo exhibition at MoMA PS1, The Fault of Formation.

Plastic film stuffing, paper fragments, mophead fibers, and glass beads bisect the canvas of Out of the Gap Where Darkness Echos, Mustangs Took Off Running (2023) to form a horizon line. A blue opening anchors the painting at the top, under which strobing blisters of white paint drip down the canvas. Martinez considers this work an homage to a “failed painting” they made before leaving New York City, where they lived and worked for fifteen years before returning to Texas in 2019. Much like the equine mark, this painting presented an opportunity to see anew, to queer linear notions of time and desirability by returning to the fleeting past in order to drive towards the future. 1 In this manner, Martinez recalls theorist Jack Halberstam’s assertion that “in true camp fashion, the queer artist works with rather than against failure and inhabits the darkness.” 2

Leslie Martinez. *Out of the Gap Where Darkness Echos, Mustangs Took Off Running. *2023. Acrylic, sumi ink, modeling paste, used studio rags, canvas scraps, used studio clothing, plastic film stuffing, polyester sewing threads, paper fragments, mop head fibers, paint chips, buckwheat hull, iron silicate, pumice, and glass beads on canvas. Photo: Kris Graves

This darkness is everywhere in Martinez’s work—as is light, and the collision of the two. I often hear people say the work reminds them of an underwater world or a telescopic view of the cosmos. Others see a topographic map, an earth pockmarked by centuries of volcanic activity. Underlying these natural readings are gashes, fissures, and explosions from which new matter arises. Much like the borderlands Martinez grew up in, described by theorist Gloria Anzaldúa as the physical and conceptual place “wherever two or more cultures edge each other,” there is no either/or in these works, but rather the constant pressing against and clashing of opposing forces, of materials and histories that weren’t meant to coexist. 3

Embracing these productive tensions, Martinez’s titling of the exhibition speaks both to the earth’s fault lines and the fractures wrought by a nation built on binary politics. Yet from these opposing forces is also born hope, and the belief that something else can—must—arise from chaos and violence. “I take a creation, formation...sort of world-building type of approach to painting,” 4 says Martinez, who builds up piles of used rags, paint chips, and cut-up hand towels in their studio. This no-waste ethos ensures that anything that comes into the studio will come out in future paintings. Their methodology embraces circularity, which includes failure.

It can be tempting to then read these works as a response to environmental degradation, or as part of the neoliberal “reduce, reuse, recycle” discourse that dominated the nineties. However, Martinez is more invested in an economy of means, one that Chicano theorist Tomás Ybarra-Fausto described as a “resourcefulness sprung from making do with what’s at hand (hacer rendir las cosas),” in which “things are not thrown away but saved and recycled, often in different context[s].” 5 In our initial studio visits, Martinez and I would often giggle over shared customs from growing up in defiantly inventive households: old containers that housed sewing materials, weights made from coffee cans and concrete, toilets repurposed as planters—detritus fostering new life. These items marked our families’ enduring creativity, an ability to build worlds through recombination. Creating from what was available became a refined alchemical process, one that would become integral to the way Martinez constructs paintings with discarded materials.

The earliest work in the show, Pour Shadows into Valleys — Dust Light on the High Reliefs (2020) recalls the legacies of postwar abstraction in which artists often deconstructed canvases to expand the possibilities of painting, unfettering it from the confines of what was possible with a brush. Reflecting on his Drape paintings, to which Martinez’s sculptural works bear some resemblance, artist Sam Gilliam recalled: “I was trying…to deal with the canvas as material by folding it, crushing it, using it as a means to a tactile way of making a painting.” 6 Created from whatever materials were available—old bedsheets, painting rags, acrylic, and used studio clothes— Pour Shadows into Valleys — Dust Light on the High Reliefs (2020) actualizes Martinez’s initial efforts to turn fabric into paint.

Martinez piles textiles that are sprayed with diluted paint and adheres them to a stretched canvas. They combine scraps and paint chips, saved and hardened over many months, with industrial materials such as sawdust and iron oxide to build up the surfaces. By including their work clothes and materials common from construction sites, Martinez nods to histories of generational labor in a celebration of craft practices learned from their family, who has worked in Texas for generations as farmers, ranchers, seamstresses, and construction workers. Through material citation, Martinez keeps their memories alive. Offering potential on the horizon for discarded materials, these works nod to both the past and the future; they are specters of a Muñozian utopia, a liberated visuality that forces us to look “beyond the limited vista of the here and now.” 7

While creating their largest work to date—the monumental, eight-paneled The Reconstitution of Rejected and Refracted Voids (2023)—Martinez watched Selena’s legendary 1995 Houston Astrodome performance. In a single take originally aired on the American Spanish-language television network Univision, the concert was the Tejana icon’s last, before she was tragically killed. Ahead of songs from her experimental album Amor Prohibido (1994), Selena opened the event with a disco medley that included Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive” and Donna Summer’s “On the Radio.”In a story that has now been cemented in pop culture lore with a Netflix series, the conversations that followed straddled the difficulties and possibilities of ‘crossing over’ to a mainstream anglophone audience from culturally-specific, Spanish-language music. These narratives bear striking resemblance to those surrounding the evolving Latine art canon today. Selena’s disco medley offered a glimpse into what could have been, whereby she capaciously expanded the bounds of what a Latine artist was expected or allowed to do. Citing both disco and cumbia, genres born out of Black and Indigenous resistance movements, she accelerated us into the future. Like Selena, Martinez’ works embody a politics of refusal, identification, and disidentification, citing influences as far-ranging as Jack Whitten’s tessellated paintings and the glittery purple jumpsuit—made by her mother—Selena wore at the Astrodome.

Leslie Martinez. The Reconstitution of Rejected and Refracted Voids. 2023. Acrylic, sumi ink, used studio rags, canvas scraps, used studio clothing, plastic film stuffing, polyester sewing threads, paper fragments, mylar balloons, iron silicate, iridescent cellophane, crushed charcoal, paint chips, saw dust, pumice, modeling paste, mica flakes, mica powder, and iron oxide on canvas. Photo: Kris Graves

“I think about Brownness as citation… as a swarm of singularity,” remarked Sandra Ruiz during a conversation with writer Raquel Gutiérrez on her book of critical essays Brown Neon (2023). 8 As I listened to this conversation, I closed my eyes and conjured up Martinez’ works, remembering how I felt the first time I saw them in person. There was so much history, futurity, and singularity in every color, fold, and gesture.

In awe, and somewhat put off by the abject maximalism, a visitor asked me recently how Martinez knew when a work was done. “When they’ve made the most out of the least,” I replied coyly, imagining Martinez’s mustangs emerging from the darkness, a band of horses roaming freely through the Texas landscape, reified from a single fleck. 9

Leslie Martinez. Untitled. 2021. Acrylic, fabric, paper, fine ballast, pumice, and iron oxide on canvas. Photo: Kris Graves

[1] Jack Halberstam writes that “queer time is a term for those specific modes of temporality that emerge…once one leaves the temporal frames of bourgeois reproduction and family, longevity, risk/safety, and inheritance”, For a critical understanding of “queer time” as a subversion of normative chronologies of progress and expectations, see Halberstam, In Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 20.

[2] Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 96.

[3]Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 2012).

[4]Leslie Martinez, Interview with Anthony Graham, The Modern Art Notes Podcast, podcast audio, January 4, 2024, https://manpodcast.com/portfolio/no-635-leslie-martinez-alexis-smith/

[5]See Tomás Ybarra-Fausto, “Rasquachismo,” in Chicano and Chicana Art, ed. Jennifer González, C. Ondine Chavoya, Chon Noriega, Terezita Romo, (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2019), 86

[6]Sam Gilliam, Interview with Donald Miller, “Hanging Loose, An interview with Sam Gilliam,” ARTnews, January 1973.

[7]José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York and London: New York University Press, 2009), 22.

[8]This conversation took place on February 17, 2024 at Inga Bookstore in the historically Chicane neighborhood of Pilsen in Chicago, where I happened to be in town for a conference. To learn more, listen to a conversation between Raquel Gutiérrez and Leslie Gutiérrez that took place on November 18, 2023 at MoMA PS1 .

[9]Amalia Mesa-Bains considers Ybarra-Fausto’s concept of rasquachismo as where “the irreverent and spontaneous are employed to make the most from the least…a stance that is both defiant and inventive…the capacity to hold life together with bits of string, old coffee cans, and broken mirrors in a dazzling gesture of aesthetic bravo.” Mesa Bains, “Domesticana: The Sensibility of Chicana Rasquachismo,” in Chicano and Chicana Art, ed. Jennifer González, C. Ondine Chavoya, Chon Noriega, Terezita Romo, (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2019), 92.