Love Rules

24 de abr – 6 de oct, 2025

- Pasado

- Exposición

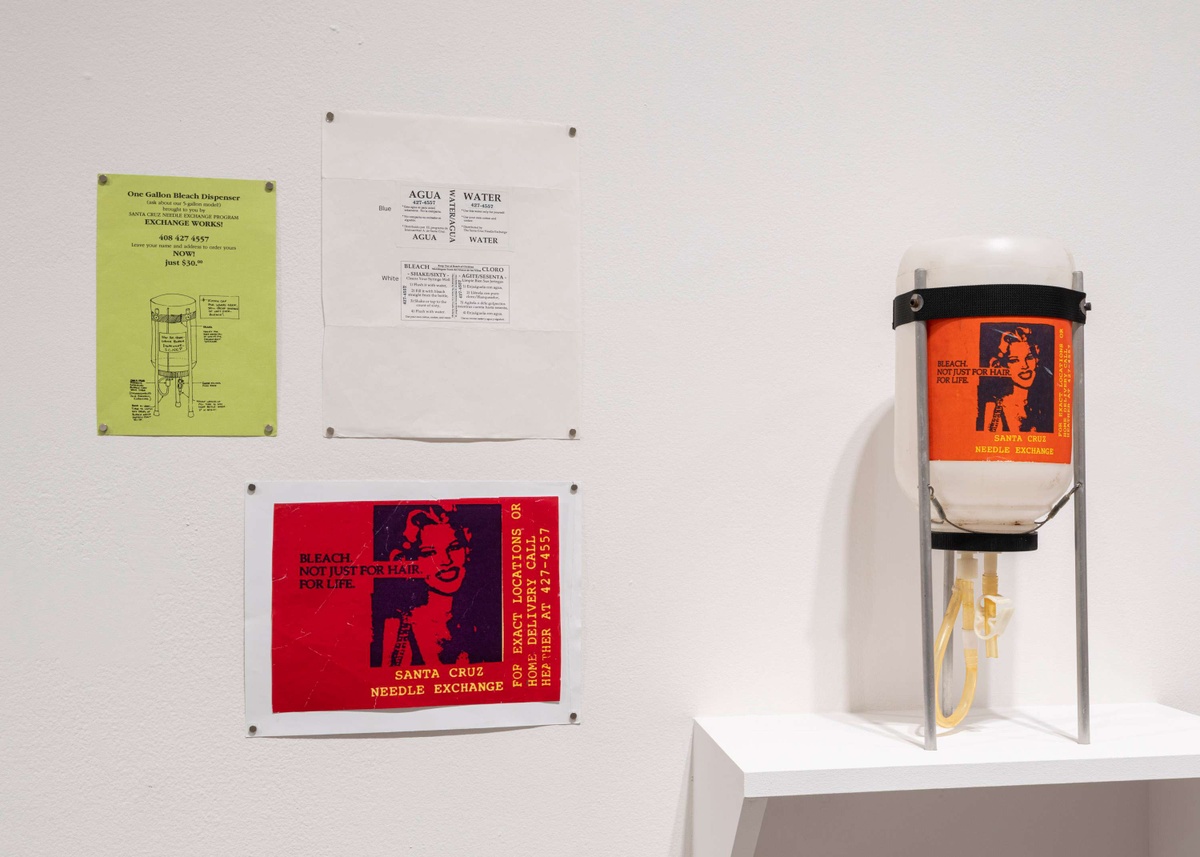

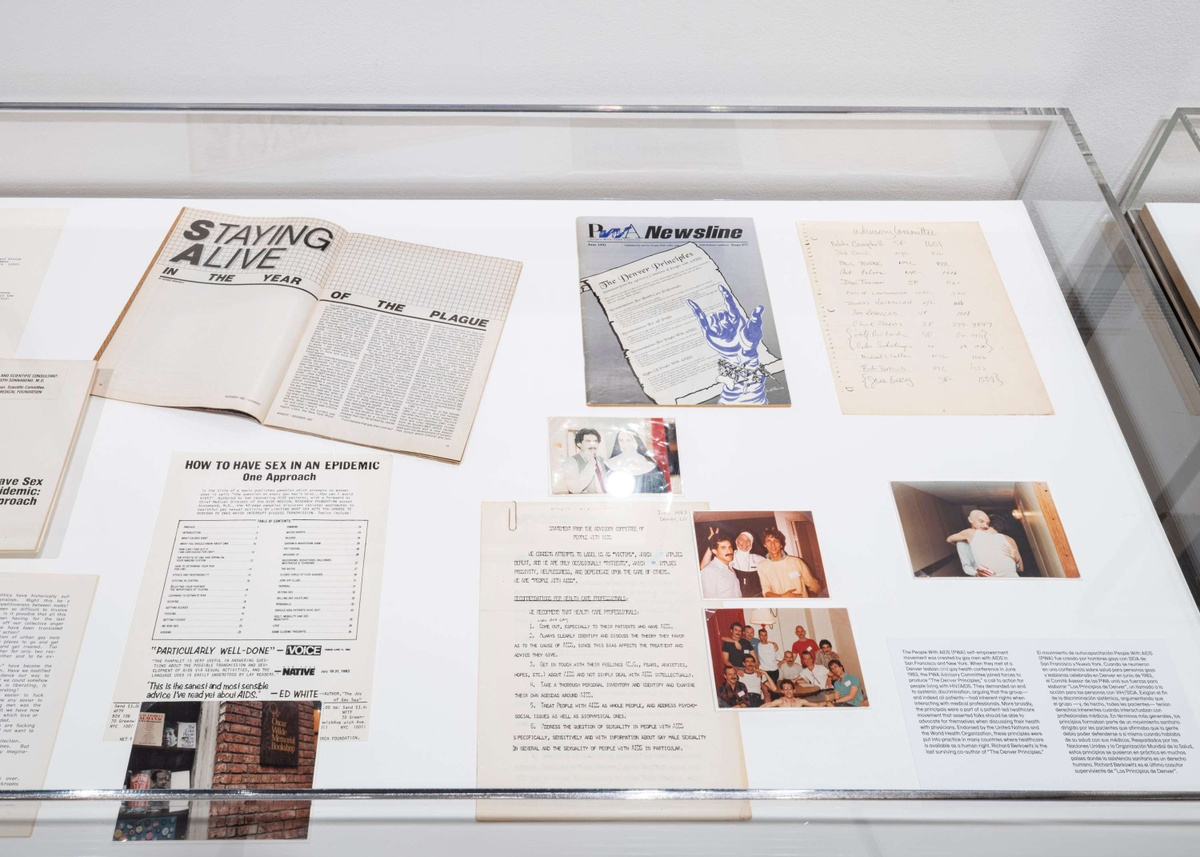

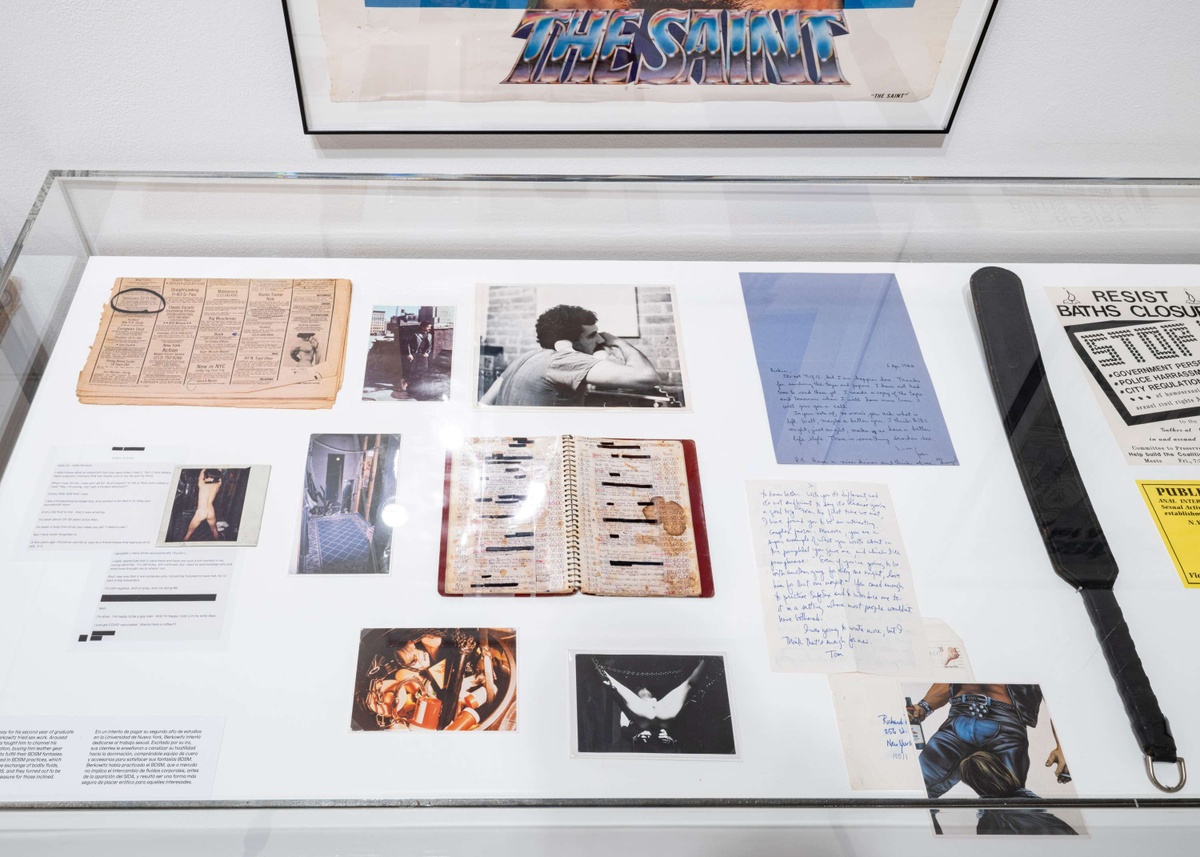

Visual AIDS presenta una exposición en Homeroom que traza los inicios del desarrollo y el impacto de los programas de reducción de daños en Estados Unidos a finales del siglo XX. Establecida en 1988, la organización Visual AIDS utiliza el arte para combatir el sida, fomentando el diálogo, apoyando a artistas con VIH y preservando su legado, porque el sida no se ha acabado. Tras su presentación inaugural en Homeroom en 2021, esta exposición muestra materiales de archivo de los escritores y activistas Richard Berkowitz y Heather Edney (fotografías, publicaciones hechas por ellos mismos y otros materiales efímeros) que detallan la creación de directrices sobre prácticas más seguras de inyección y sexo. Centrada en la experiencia de trabajadoras sexuales y consumidores de drogas, la presentación destaca cómo las estrategias de reducción de daños que utilizan los servicios sociales hoy en día se basan en el trabajo de las personas más directamente afectadas por la epidemia del sida y las sobredosis relacionadas con las drogas.

Fechas

24 de abril–6 de octubre, 2025

Lugar

MoMA PS1

Parte de

Crédito

Organizada por Blake Paskal, director de programas, Visual AIDS; y Sheldon Gooch, asistente curatorial, MoMA PS1; en colaboración con Greg Ellis, archivista y curador, Ward 5B

Love Rules: The Harm Reduction Archives of Heather Edney and Richard Berkowitz sucede a la presentación inaugural de Homeroom, realizada por Visual AIDS en 2021.

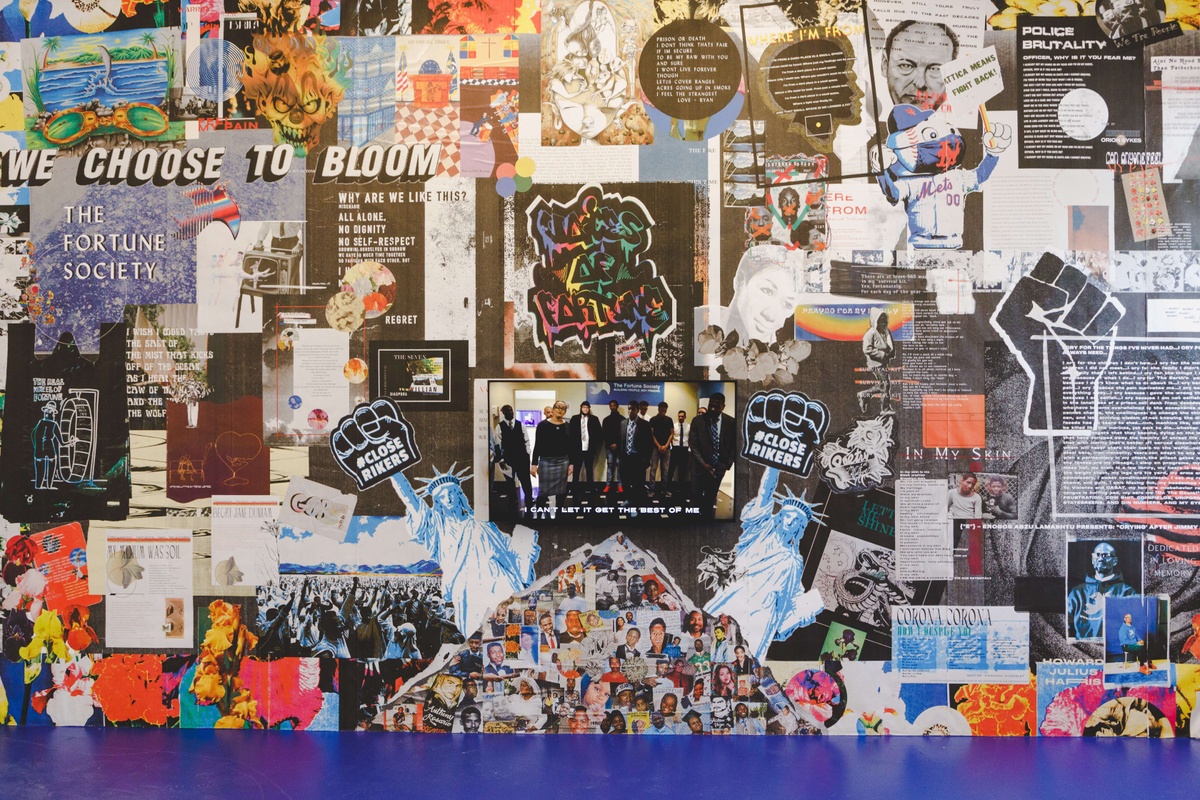

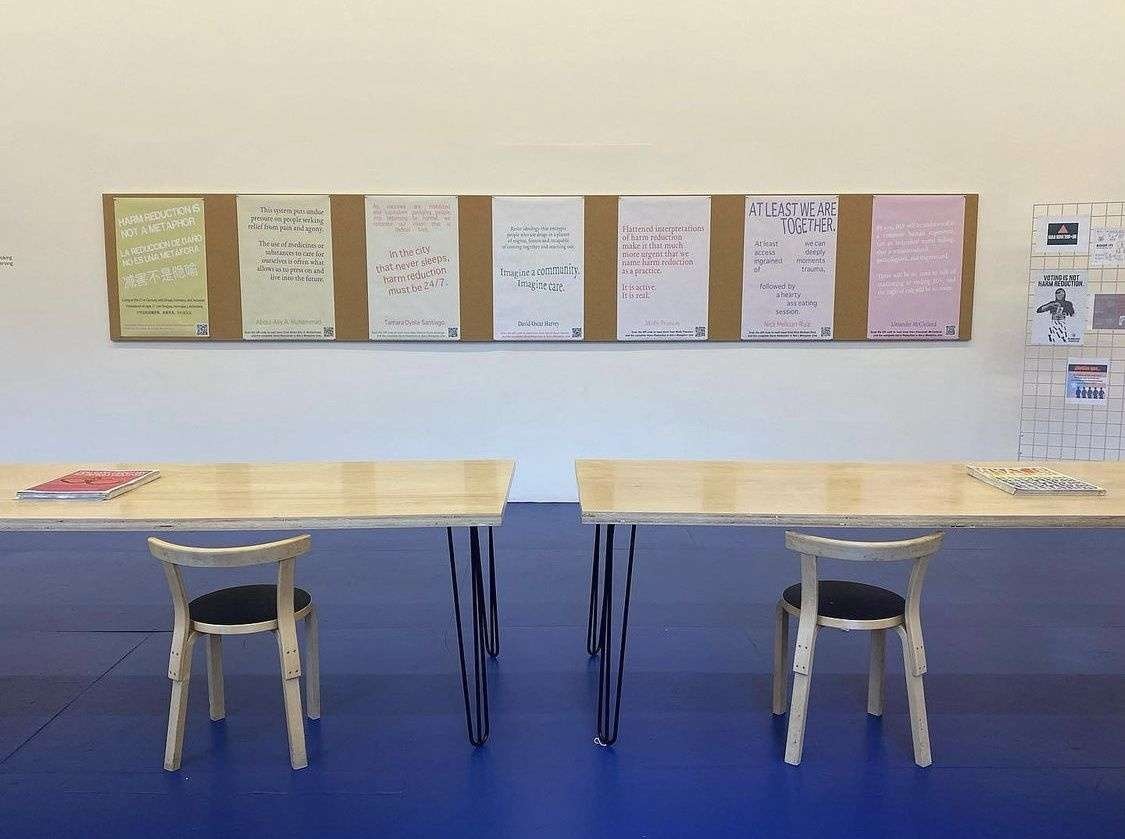

Vistas de la instalación

Installation view of Love Rules: The Harm Reduction Archives of Heather Edney and Richard Berkowitz

Installation view of Love Rules: The Harm Reduction Archives of Heather Edney and Richard Berkowitz

Installation view of Love Rules: The Harm Reduction Archives of Heather Edney and Richard Berkowitz

Installation view of Love Rules: The Harm Reduction Archives of Heather Edney and Richard Berkowitz

Installation view of Love Rules: The Harm Reduction Archives of Heather Edney and Richard Berkowitz

Installation view of Love Rules: The Harm Reduction Archives of Heather Edney and Richard Berkowitz

Installation view of Love Rules: The Harm Reduction Archives of Heather Edney and Richard Berkowitz

Installation view of Love Rules: The Harm Reduction Archives of Heather Edney and Richard Berkowitz

Audioguía

Love Rules Audio Guide

:

Blake Paskal, Exhibition Co-Curator

Blake Paskal: Hi, my name is Blake Paskal. I’m the Programs Manager at Visual AIDS, and I am one of the co-curators of this exhibition. The harm reduction work that is emphasized within this exhibition is drawn from the work of two individuals: Heather Edney and Richard Berkowitz, both of whom provided critical texts that aided in harm reduction practices. So while these harm reduction practices had been tested and were being utilized by communities directly, the texts that are central to this exhibition, How to Have Sex and Getting Off Right, reflect the earliest distillation and codification of these harm reduction practices into printable material.

I think one of the biggest takeaways of this exhibition is that it affirms: it’s on us to provide solutions for ourselves and to take care of ourselves and to take care of our communities. And at the current political moment that we are at, it can be hard for people to see a way forward or to imagine how we can operate without the assistance of institutions when the individuals in this exhibition show us that when community stands together, we can create our own solutions.

Hi, my name is Heather Edney. I served as the executive director of the Santa Cruz Needle Exchange from 1990 to about 2003. And throughout the time that I was working with the Santa Cruz Needle Exchange, I worked with all these different artists. We created all of these incredible educational campaigns. And when I left Santa Cruz, I was very strung out. I was coming back to LA, I was homeless, I was living out of my car, and I had everything packed in these boxes. And when it was time to go into treatment, I just schlepped everything in with me. I asked my…kind of demanded that my caseworker hold onto everything for me because, I didn’t know why, I just knew I needed to keep this stuff. So she stored everything under her desk for six months, which is crazy because in treatment programs, they don’t break rules for you because “you’re not special.” Anyway, that’s a whole other thing. But she knew this was very important to me, and it was important to me, but I didn’t know why. I just knew I needed to keep the stuff.

So decades go by and I am just bringing this stuff from one place to another. Going to sober living, moving into house, 1, 2, 3, whatever. And then COVID happened, and Greg Ellis contacted me. He is an archivist and curator and asked if I had a set of zines and could I send him a copy? And I ended up sending him my whole archive. And then I started to understand, oh, this is something that people who are into this kind of thing would appreciate. Anyway, so it was like a whole other story.

So Harm Reduction has been co-opted by “the straights.” People who have their shit together, they’re researchers, they have access to resources. So the Harm Reduction movement or this type of intervention has been mainstreamed. But the people who thought of everything were people who use drugs who did not have access to resources. We were just saving our lives, saving the lives of the people we love. So I’m hoping that younger people or newer people to Harm Reduction, or just people who care about people who use drugs come in, they see this stuff and they’re like, “Oh, this person who had a lot going on, she thought of all this stuff.” That’s where these ideas came from.

So much of Harm Reduction, the things that are foundational, are in that room. And it took me while to understand I am the one that thought of this. I didn’t really ever until that was pointed out to me. So that is the thesis of all of this, is that the answer is always going to be with the community that’s impacted.

I hope it is inspirational to other people who are creative, who don’t have it all figured out to… don’t stop. Create. Just do it. If you’re trying to save lives or to help other people, you can’t really do it wrong. And I hope that this exhibit, if someone felt like they needed permission, that this could be that. I did not have it on lock. I still don’t have it on lock I do a little bit more now than then, but barely.

So the other thing is, I was a chronic overdoser. I should have died dozens of times over. I didn’t. I’m alive, and I’m still doing this work today. And I know that PS1 does these kinds of things with the community all the time, but this is such a big deal for this community that I’m a part of. We don’t ever receive institutional recognition or legitimacy, it just doesn’t happen. So this is exciting. I know this is going to, it will matter, I think. Yeah, I hope.

Richard Berkowitz: My name is Richard Berkowitz, and I want to welcome you to the history of the invention of the first safe sex guidelines to stop the sexual transmission of AIDS. Here’s a synopsis of what you’re looking at and how it came about. In August 1982, my doctor, Joseph Sonnabend diagnosed me with early symptoms of AIDS. Everything I read said no one survives. I was 26. I told Dr. Sonnabend, “I knew I was doomed,” but Sonnabend told me that AIDS was new, so there were no experts. So why did I believe I was doomed? Was I stupid enough to believe whatever I read?

Suddenly I had hope. I went to work in his medical practice and discovered that Sonnabend was a world-class virologist with a distinguished history in lab research. He introduced me to another patient, the late Michael Callan, to write and alert gay men. On November 1982 article, We Know Who We Are, called for the end of urban gay male promiscuity, but I had doubts. Three months earlier, I was a sex worker trying to pay for grad school at NYU until I woke up to AIDS, stopped having sex, and disconnected my phones.

One night, a client rang my doorbell. I explained AIDS to him and assumed he’d fly out my door. But instead he asked, “Can’t you just put on your leather and boots, let me worship you and jerk off?” As soon as he left, I ran to my typewriter and typed: How to Have Sex in an Epidemic. That was my eureka moment in December 1982. Every day at Dr. Sonnabend’s frantic office, while he was treating sick, dying in AIDS-panic gay men, I began pestering him about ways to make sex safe. “Is sex all you care about,” Joe yelled at me. “No, but I had nurtured a close circle of friends and lovers who were my gay family, who I wanted to protect and grow old with,” so I kept on pestering Joe until one day he exploded. “All my patients who have a history of oral and penile sexually transmitted infections are not showing signs of AIDS. It’s only my patients with a history of rectal STIs who are.”

After that bombshell sunk in, receptive intercourse was the risk. I was able to finish writing How to Have Sex in an Epidemic. In February 1983, when Mandate Magazine decided to publish my article, Sonnabend recognized its importance, but it took 10 months for my article to appear, and I refused to wait. That’s when Joe had the idea to publish it ourselves. He got Michael Callan to join us and turned my article into a booklet we self-published in May 1983. At that time, America had 1,400 cases of AIDS, 558 deaths and 70% were gay men. Our guidelines worked. So what happened? Gay leaders who had publicly encouraged the gay sexual revolution of the 1970s hated us for writing in We Know Who We Are, that promiscuity was causing AIDS in gay men, so they blacklisted us for our mistake instead of confronting their own. They unwittingly contributed to the deaths of their own people.

When a new epidemic appears, scientists examine the evidence and propose theories to minimize risk. Theories are just frameworks. They’re often wrong in detail, but they’re all scientists have when people start dying, and we need ways to limit sickness, death, and contagion. Joe used cytomegalovirus or CMV as a model. When HIV was discovered three years later, it spread the same way as CMV, entering the bloodstream from receptive intercourse with infected partners. So Dr. Joe was right about the risk of receptive intercourse, and that’s what scientific theories can accomplish if people without scientific expertise, gay or straight don’t get in the way as they did with our invention of safe sex guidelines. Joe taught me and Callen that in science as in life, there’s always more to learn, that the nature of being human as we all make mistakes, but that’s how progress gets made.

I was 26 when I told you I was doomed. This year I turned 70. How to Have Sex in an Epidemic came too late from many of my friends and Michael Callen, but millions of lives were protected and saved from the sexual transmission of HIV and many other sexually transmitted viruses and infections too. Everyone has heard of safe sex, but few have ever known how it came about. Now you have, and you also got to meet Dr. Joseph Sonnenbend and Michael Callen, survivors of catastrophes who often have a need to testify, a need that can wear out the strongest among us. That’s why this exhibit and you who came to view it, give me a deep, appreciative, overwhelming sense of peace. Sometimes it’s best to just lay out the evidence and let people decide for themselves. Thank you.

Contenido relacionado

Programas Relacionados

Homeroom: Slow Factory

The Revolution is a School

Homeroom: Queensbridge Photo Collective

Still, Like Air I'll Rise

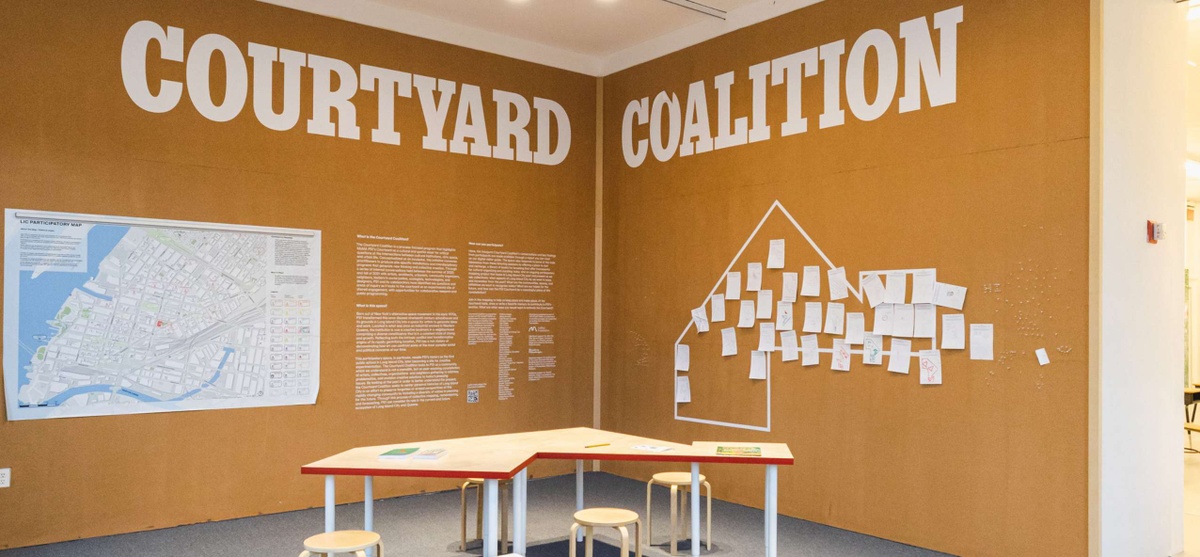

Homeroom: Courtyard Coalition

Homeroom: The Fortune Society

Homeroom: Nuevayorkinos

Essential and Excluded

Homeroom: Black Trans Liberation

Memoriam and Deliverance

Homeroom: Visual AIDS and What Would an HIV Doula Do?

Homeroom: The Lower Eastside Girls Club & jackie sumell

Freedom to Grow

Homeroom: Malikah

Homeroom: Teen Art Salon

A Protospective

Homeroom: Little Manila Queens

Mabuhay!

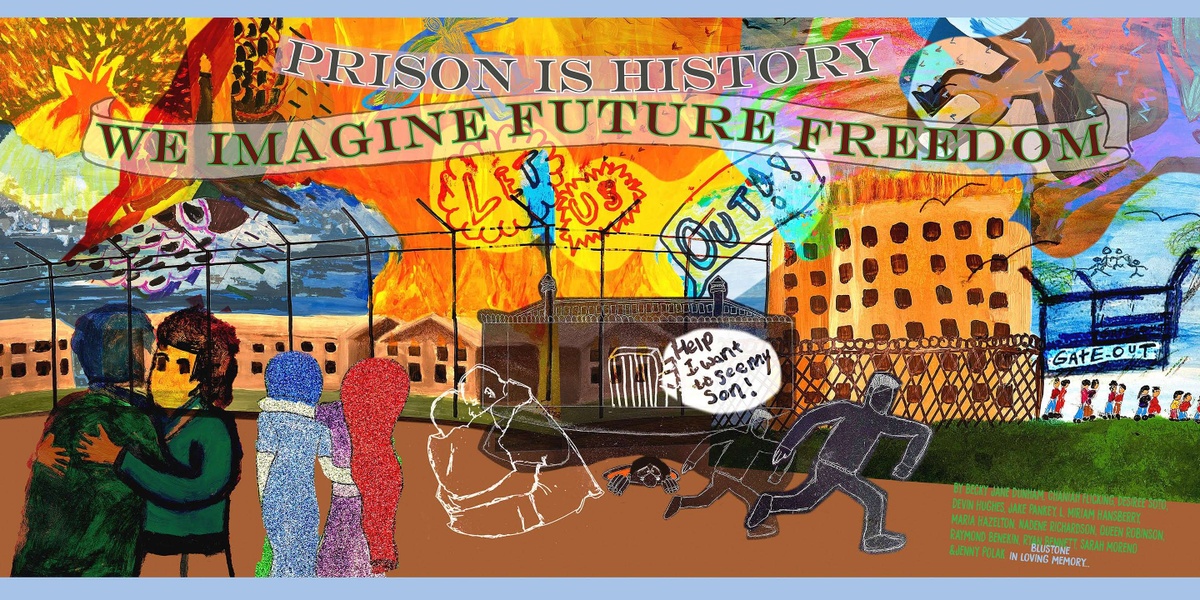

The Fortune Society: Future Freedoms

Future Freedoms

Homeroom: LA ESCUELA___

Education as Resistance