Life-Work in Motion

- Texto

Gabrielle Goliath’s practice is oriented around social and affective encounters. Her work contends with issues of representation and the legacies of trauma and violence endured by Black, brown, femme, queer, and vulnerable people. Engaging sonic and serial forms, Goliath upends notions of history as a singular resolved narrative. The most recent cycle of Goliath’s project Personal Accounts (2024–ongoing) is on view at MoMA PS1 through March 16, while a chapter of her ongoing ‘life-work’ Berenice (2010–ongoing) was featured in New Photography 2025: Lines of Belonging, the latest edition of MoMA’s celebrated contemporary photography series. On the occasion of these presentations, the artist spoke with Ruba Katrib, MoMA PS1’s Chief Curator and Director of Curatorial Affairs, and Oluremi C. Onabanjo, MoMA’s Peter Schub Curator of Photography, about the collective forces and commitments that shape her work.

Ruba Katrib: Since Berenice was recently acquired by MoMA and just on view in New Photography 2025, let’s start with a discussion of this work. It is really fascinating to see the connections between that ongoing project and your exhibition at PS1—there are a lot of parallels.

Gabrielle Goliath: Berenice is what I refer to as a ‘life-work of mourning,’ directed toward my childhood friend, Berenice, who was shot at home in an incident of domestic violence. As a young artist, I grappled with how to recall this life—not so as to preface it with violence, or to return to that scene of subjection or spectacle, but to do something else. Berenice is a work of channeling, an invocation of absent presence that, for me, really counters the kind of fixity we so often associate with photography. It pushes at the limits of the frame, as those who come and stand in for Berenice and gift something of themselves.

Oluremi C. Onabanjo: Each iteration of Berenice has a relationship to another. There’s the clear gesture of a woman standing in for someone whose life is going onwards, unlived. But each stanza, if one might call it that, has its own formal and processual conventions. How would you get in contact with the people who stand in for Berenice?

Gabrielle Goliath: Berenice is very much a work of community, grounded in the relational labor of those who come to this personal story of loss and consent to offer themselves to the work. Many of the Black and brown women or femme-identifying individuals who have collaborated over the years are fellow artists, poets, writers, friends, or family. Others I approached in the street or the aisle of the grocery store, asking: Well, would you come? Would you gift yourself? Would you be a surrogate and stand in for the absent presence of Berenice? And of course, their generosity in responding has made the work possible. And they were moved, especially I think because of that capacity of violence to de-subjectify, to render statistical, anonymous, numerical. For me, that’s always been bedrock to Berenice, and to the rest of my practice in fact, this commitment to specificity, to the person, and in this case, Berenice.

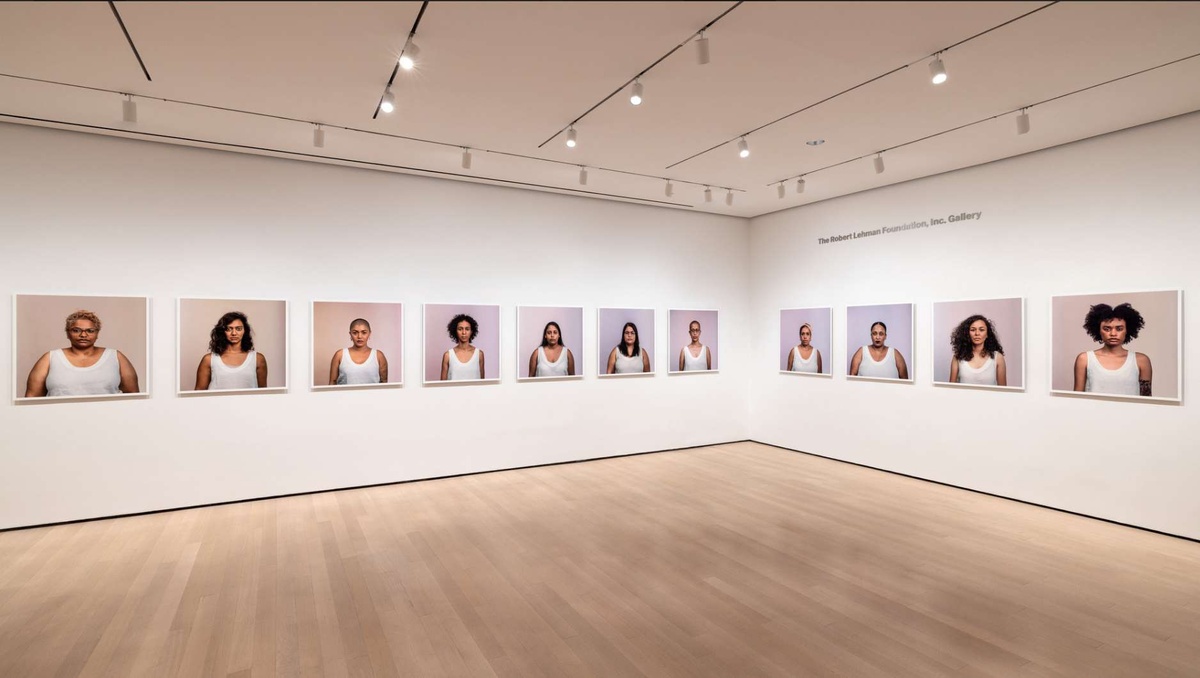

Before I began this work back in 2010, I met with Berenice’s mother and sister and gained their blessing. It was a very hard conversation, as you can imagine, but so necessary. And I will never forget the moment they came to the first exhibition of the work in Johannesburg and communed with the images, I really don’t have the words…There is something particularly funereal about that first cycle of portraits: black and white, all 19 women wearing the same white vest. The next cycle, Berenice 29–39, introduced color, and that felt important, but similarly, I asked each individual to wear the same white vest. So in all of the images, including the three I most recently produced, there are strong material and formal registers, as in different ways this same commemorative gesture is performed.

Oluremi C. Onabanjo: You appear in all three cycles of Berenice. How do you consider your relationship to this body of work?

Gabrielle Goliath: The morning after Berenice was killed we visited the family, and when her mother saw me, she called out Berenice’s name, not mine. And then she embraced me—for what felt like a lifetime. So, this name, Berenice, was spoken over me, is something I bear, which is why it is imperative that I participate in the work, and then invite others to join alongside me as we hold that name in chorus, and image by image speak it over others.

Oluremi C. Onabanjo: Personal Accounts was the first work of yours that I experienced, at the 11th edition of the Rencontres de Bamako (2017). It was absolutely transfixing, and it means a great deal to now see a later cycle here in New York. While in many ways Berenice is about presencing, I feel there’s this sense of annotation and redaction that evinces a very clear ethical commitment in Personal Accounts.

Gabrielle Goliath: Yes, in withholding words and narrative, Personal Accounts really asks us to think and feel differently about presence—about what it means to relate or identify in terms of a certain unknowing. When I first produced Personal Accounts in 2014, I was really grappling with this problematic dichotomy of the so-called voiced and voiceless, and thinking rather about those transparent conditions that render certain voices inaudible, invalid, or irrelevant. I was thinking about how the accounts of survivors are so regularly discredited, not believed. And in thinking about that, I wanted to explore what foregoing lexicality may enable. What then becomes possible? Could such an intervention help to shift those conditions of relation, of believability?

In that first iteration, I worked closely with a group of Black and brown women, all survivors of racial-sexual violence. One of them was my mother, in fact. So yes, again, this work is personal. Since then, the work has travelled and grown, and wherever it sounds it gathers community. I realized that there’s something about this work that needs to become transnational in scope—enabling forms of allyship, without collapsing the very significant differences that exist between the different cycles, spaces and individuals.

Ruba Katrib: In Personal Accounts, the work behind the work is so extensive. I am sure a lot of the experiential quality of the work developed from that initial concept and methodology. These are projects that have significant duration in terms of production. You allow yourself the freedom to evolve and change how the work looks and how you approach it through the years. So of course it will change and evolve and adapt if you allow it to, right?

Gabrielle Goliath: Absolutely, the work shifts and modulates over time, as each cycle comes about in dialogue with collaborators and in response to sometimes very different contexts. That gesture of shared accounts and our mutual agreement to withhold the spoken words is common, a kind of grounding exercise throughout the series. But how that plays out is really worked out in a very relational process. It is the work behind the work, as you say. In Tunis, for example, none of my collaborators wished to be visually represented, and so the emphasis is more sonic and spatial. In other cases, claiming a certain visibility has been an important political imperative. But certainly, the durée and scope of this project demands that I remain responsive.

Ruba Katrib: Considering this transnational, global element, it’s brilliant how everyone is probably speaking different languages, but there’s no translation. There are no subtitles. There’s a kind of non-linguistic modality. The language barrier is erased, even though it probably was there at some point in the process. It’s really fascinating because as a viewer, you are immediately put into this mode of dialogue that’s less registered, but is actually critical to communication: body language, fillers between words, that space of thinking before speaking. You’ve withdrawn the conditions for epistemophilia, the desire to want to know the story and what is everyone saying, and thus foreclosed questions around whether they are telling the truth or not. We are able to see something else, something that is harder to put words around.

Gabrielle Goliath: Yes, something shifts as that language barrier is removed. Of course, a certain difficulty is introduced in the absence of narrative, and yet that opens up a different opportunity: encouraging a kind of knowing grounded in what we cannot know of each other. And yet we can relate by stepping into those in-between spaces we share: of breath, of vulnerability, and of presence. And there is agency in this gesture of withholding—for many of those who chose to collaborate, the opportunity presented a safe space of sorts, allowing collaborators to share with vulnerability and without fear of reprisal. There is, however, also an online archive of additional survivor offerings on my website (also available on the artwork labels), as an alternative space for sharing, where you’ll find a range of quotidian practices of survival shared by collaborators: playlists, recipes, poems, photographs, artworks, and yes, harrowing accounts of survival and repair. These are in English, Arabic, Albanian, Italian, Ukrainian, Bengali, and other languages.

Oluremi C. Onabanjo: Upending narrative, to me, taps into the paralinguistic. You have a recurring interest in sound and sonics, but not necessarily in narrative, and the sense of completion it might offer. The sculptural installation of the screens, which lean and slant against the walls, also feels almost anthropomorphic.

Gabrielle Goliath: There’s something really significant about the repose of these screens, and their scale. It encourages an encounter that feels human and relational, through not only what is imaged, but what is experienced somatically. And yes, in the same way that the work foregoes narrative, it forgoes a kind of choreographic order, as the work is not arranged or composed sonically, but rather convened in more haptic ways. Each cycle is beautifully singular, but of course shared, opening spaces for implicated, tender, and I hope, transformative encounters.

Ruba Katrib: When I’m in the space, I feel quite strongly that the work is not just a document, it’s actually alive. It’s never the same at any moment because the cycles are not synced up. The way you’ve created a live composition amplifies the intensity of the work and the presence of its subjects. You really feel like you’re walking into a room and these presences are here, and you have to really contend with that. It can be moving and uncomfortable and emotional and also very human. How are people prepared for this shoot?

Gabrielle Goliath: I love that. The work really does breathe and cycle, and the resonances and dissonances between the cycles is in constant play. In terms of that convening work, I spend a great deal of time with each collaborator in advance, introducing them to the work and speaking them through the processes and implications of sharing their account. It’s conversational, and we agree on terms and conditions that shape the work and how each cycle comes to be, look, feel, and sound. Self-presentation is key, and this extends from whether or not individuals wish to be shown, or how, in terms of dress, make-up, etcetera. And, of course, this further extends to what they choose to share on the day—for some it’s a song or chant or poem, for others it may be testimony or a prayer. I do encourage them to consider wearing something blue, even if it’s just a touch. But again it’s not a rule. Advocate Adila Hassim just doesn’t do blue, for example, but shared her transfixing account in beautiful shades of plum!

Ruba Katrib: They’re self-fashioning. How they are presenting themselves in this moment in which they’re telling their story is really important.

Gabrielle Goliath: Absolutely, and that allowance can really push the work. In the Kyiv cycle, for example, one of my collaborators enlisted in the army a few weeks after I filmed their account. They are queer and connected to the LGBTQIA military and were nervous of showing their face in the work, given what they had shared and their outspoken advocacy for queer rights. At the same time, they really wanted to remain part of the project. And so, I worked closely with my editor to shift their position in the frame. It took hours, days actually, but the result was beautiful. You see only their shoulder to one side, and yet they remain so present. It meant a lot to them as well, to be part of the cycle on these terms of adjustment, responsiveness, and care. How each collaborator is referenced in the work, is another point of dialogue and self-assertion. While most collaborators have chosen to share their names, others have opted to participate under an alias, military call-sign, or chosen name. Others have opted to withhold their names, and it has always been important for me to acknowledge the agential claim registered in that kind of decision. In this case, one participated as “a queer woman soldier who chooses to withhold her name.” And this has me thinking of what we were saying earlier about Berenice, and the idea of bearing a name spoken over you—bearing names that may not be ours but become part of us. And this labor of bearing, of transfer, must open also to names we cannot know but which nevertheless have a bearing on us. It is the demand of what I call ‘a radical familiar’—which is to say, a sociality premised on a decolonial Black feminist love-ethic.