First Hit, Slow Burn

- Writing

Dena Yago explores the ways in which images and phrases become sticky with meaning, capturing the anxieties or beliefs of a cultural moment. Her works draw inspiration from advertising, memes, classic cartoons, and the political comics of the Situationist International, a mid-twentieth century avant-garde art movement. Two of her paintings are currently featured at MoMA as part of a site-specific installation she designed for The Modern Window, located outside The Modern restaurant on West 53rd Street. To mark the occasion, she sat down with Jody Graf, Assistant Curator at MoMA PS1 and organizer of the installation.

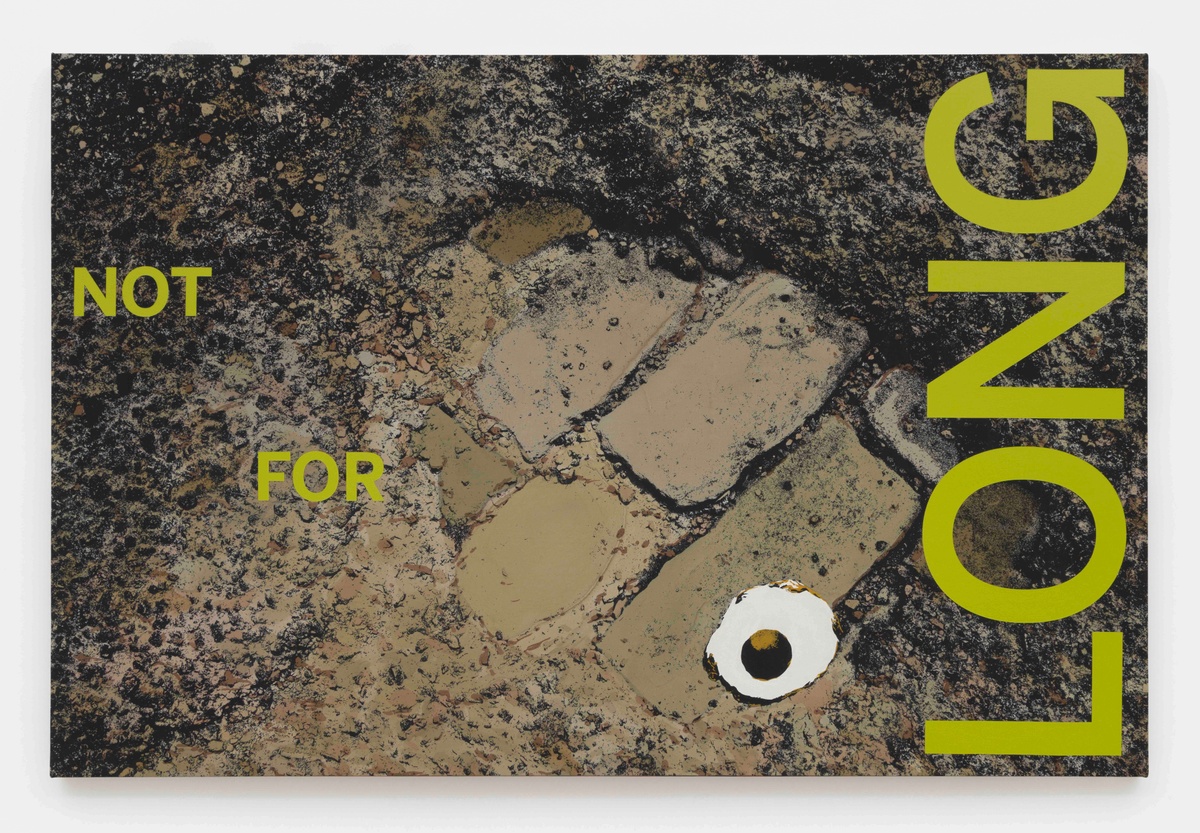

Jody Graf: Your installation for The Modern Window touches on many histories, ideas, and references, almost as if condensing them back into the “yolk” of the eggs featured in the paintings. Let’s start by talking about the eggs, which appear in two different states and contexts: there’s a close-up of a fancy dish called “Eggs on Eggs on Eggs” from The Modern restaurant, and an image of a fried egg splayed on the cobblestones outside your studio in Industry City, Brooklyn. You’ve featured eggs in past works, too, and have described their function as “harbingers,” anticipatory by nature and ripe with future meaning. Can you elaborate on how eggs perform semiotically in your work?

Dena Yago: Eggs are a visual shorthand for the precarity of potential and new life. Beyond their symbolism, materially they are simultaneously fragile and structurally resilient. The egg-as-symbol is legible across cultures and histories. Much of my work deals in symbols that are indicative of a specific social or economic moment, that are as much symptomatic of a time as well as emblematic of a certain era’s tenor. In other works, I’ve included lantern flies, last-mile delivery boxes, and oversized stuffed bears as harbingers. Here, I’m using eggs in various states—as roe, sauce, broken yolk, and sidewalk splatter—but not pictured whole, focusing more on their fragility and precariousness. Eggs are, in a sense, the highest-order harbinger, a literal shape of things to come.

JG: There is something comically self-defeating about eggs, especially the fried egg: it becomes indicative of thwarted growth and lost optimism, the collapse of boundless potential. Sunniness married with exhaustion. This is also echoed in the text that you’ve superimposed on them. How do ideas of finitude and capacity play into these works? And how do you see that relating to our contemporary moment, in which—I’d argue—a subconscious scarcity mindset leads to a kind of feverish accumulation of things, images, clout?

DY: A splattered egg is funny in a melancholic, slapstick way. They land on the ground with a thud, and I think the text should land similarly, it should ooze at the edges like a broken yolk. The two phrases, “Down for Now” and “Not for Long” are meant to be read slowly, to roll around in the mouth-mind, slipping in and out of readings. “Down for Now” can evoke a sense of down-time, dysfunction, or playfulness. The same can be said of “Not for Long.” There is a finitude in both statements, and I think what haunts both of them is a “here for a good time, not a long time” attitude that can be attributed to both a feverish YOLO mentality, as well as a very valid response to our world being completely pear-shaped in the face of social and environmental collapse.

JG: One of the reasons that I proposed your work for this site, which interfaces directly with the public space of the sidewalk, is because you have thought so incisively about the intersection of cultural and spatial shifts in urban contexts, especially New York. Can you talk about how the work responds to its context in Midtown, as well as the other neighborhoods it more obliquely references?

DY: I keep coming back to the New York City skyline. I have been photographing it from my roof for over a decade, and am interested in how it operates as a stand-in for a “generic” city, but is so information rich that it’s tethered to the ever-changing landscape of this city in particular. For these works, rather than including the skyline as the backdrop for the two paintings—which are shown at street level—I wanted to reflect the streetscape as it plays out on 53rd. I use a reflective wallpaper overlaid with a printed textile pattern (sourced from The Modern’s signature tablecloths), with the intention that this backdrop becomes a reflection of the fabric of city life. I am also quite interested in New York City’s relationship with both artists and the broader, more marketable set of cultural producers from which it extracts a lot of cultural capital. The city trades on being a cultural center, while not providing much material support for artists to thrive in terms of affordability or space. Industry City, where I photographed the fried egg, is an interesting case study: its Bloomberg-era revitalization as a post-industrial creative hub has quickly become more attractive to companies trading on the symbolic capital of cultural activity. My studio is currently a few blocks from Industry City, and I spend a lot of time people-watching there. I am interested in the language and signage meant to attract those that want to be identified as members of a specific culturally-oriented set. The iconography of these spaces—where activities such as co-working or the production of lifestyle take place—often use the language and imagery of flexibility, individualism, and unfettered growth.

JG: The typeface you chose for the text obliquely nods to another neighborhood, the Meatpacking District. How does that reference play into the piece? It’s funny to me that Industry City and Meatpacking are both areas known for their cobblestone streets. They suggest a seamless and inevitable historical transition from an era of horse and buggies to one of Theory and Sephora, papering over the shocks, disruptions, and displacements that attend these changes.

DY: The Meatpacking District is another example within New York City of a site that was used by radical communities—and hard-goods industry—whose cultural capital made the neighborhood attractive to development, who then displaced and replaced them for profit. The typeface I’m using draws inspiration from Florent Morellet’s restaurant Florent, which was open in the Meatpacking District from 1985 to 2008. Tibor Kalman and Douglas Riccardi from M&Co did the graphic design for the menus, postcards, and announcements in exchange for meals, and some of those are in MoMA’s collection. Florent was open when I first moved to New York and held a certain promise of belonging. It was a haven for queer communities, AIDS activism, and artists, but ultimately got priced out of the neighborhood whose cultural capital it helped establish.

JG: The work of course also specifically references The Modern, the restaurant outside of which it’s installed. This is, I believe, the first time that an artist invited to create work for this space has addressed the context of the restaurant explicitly. What drew you to incorporate elements from The Modern’s visual syntax into the work—and what interests you about dining establishments in general? I know you’ve alluded to other restaurants and bars in past works, too.

DY: Bars and restaurants are iconic, especially in New York City. It’s where the work happens for a lot of artists, writers, and demi-mondes more broadly, at least that’s how I’ve felt living and working here. There are signature spaces for different scenes, and I’ve included references to specific locales, dishes and drinks that play a significant role for myself and my community. When starting this work, I was thinking about the role of specific dishes on a larger social scale. I thought of this moment in late 1970s New York known as “The Pastrami Agreement,” when Governor Hugh Carey met with judge Simon Rifkind—co-architect of the Municipal Assistance Corporation—over pastrami sandwiches to come up with the Emergency Moratorium Act that would keep the city out of default, and create the financialized machine we inhabit today. Our current reality was shaped while chewing on the fat of something as both banal and iconic as a pastrami sandwich. I’m deeply interested in the mechanisms of soft power, for which the power lunch plays a significant role. The Modern is a powerhouse, decisions are made there every day that shape our world.

JG: There are so many histories embedded in the work, but it also functions on an affective level. It seems like a happy coincidence that your installation is opening while the Ed Ruscha show is on view at MoMA, because I feel the “OOF” in your work. Can you talk about the gut-punch level at which your work operates?

DY: I use language concretely, as image, and want it to unfold slowly, both visually and sonically. The words I choose, presented in particularly slow mediums like painting, have multiple intended meanings and associations. The “OOF”-ness has maybe to do with how the language and images unfurl on multiple registers. The words are meant to slip in and out of semantic satiation, and roll in the mouth-mind uncomfortably over time. They are meant to have a first hit, and then a slow burn.

Learn more about Dena Yago’s installation for The Modern Window, located outside MoMA on 53rd Street.

Dena Yago is an artist and previously a founding member of the trend forecasting group K-HOLE (2010–16). Recent exhibitions include Capacity, JTT Gallery, New York (2023); Zurich Biennial, Kunsthalle Zurich, Zurich (2023); Barbe à Papa, CAPC musée d'art contemporain de Bordeaux, Bordeaux (2023); Industry City, High Art, Paris (2022); Image Power, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem (2020); and Made in L.A. 2016: a, the, though, only, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2016). Recent poetry publications include Fade the Lure (After Eight Books, 2019). Her critical writing has appeared in e-flux journal, Flash Art, and Frieze. Yago lives and works in New York City.