Stewart Uoo’s Set Design for Warm Up 2024

- Writing

Stewart Uoo

(American, b. 1985)

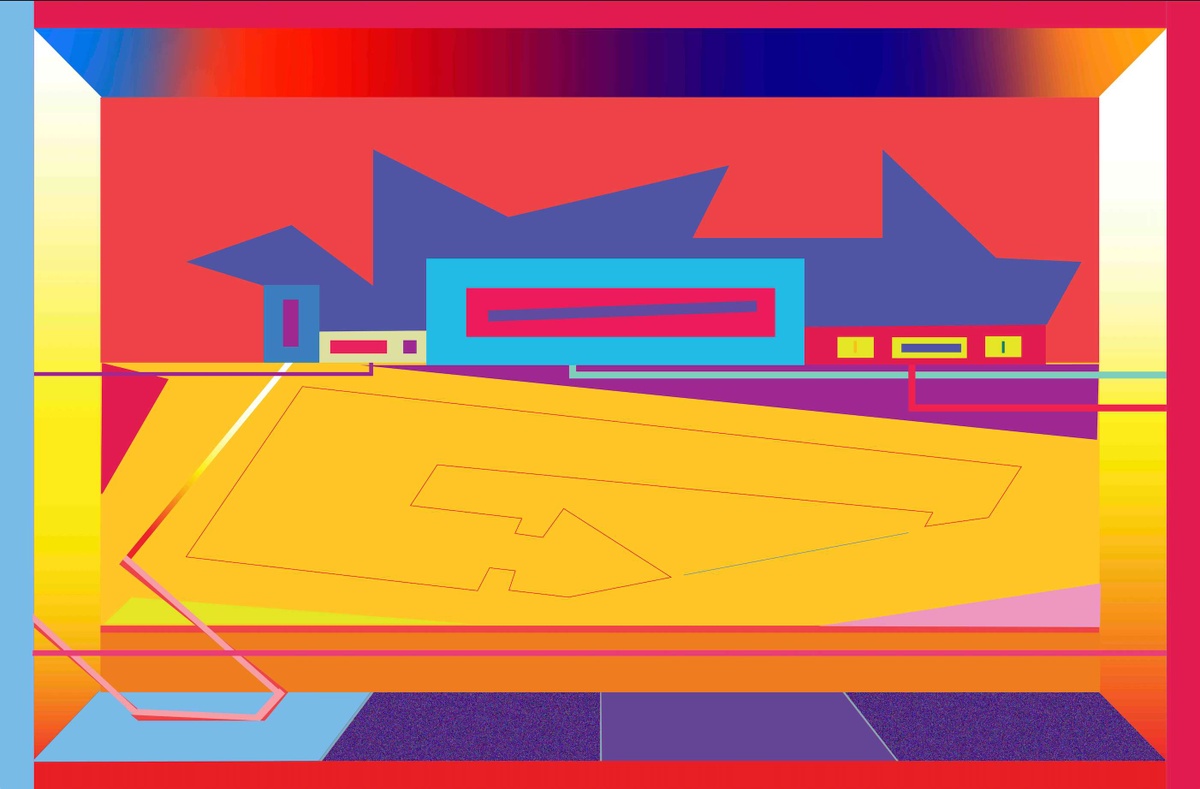

Contemplating Non-Dualism IV (Triptych) 2024

Acrylic, pigment, and collaged canvas

Used Sun (Eclipse) 2024

HDU foam, epoxy, glass and acrylic tiles, hardware, and motor

Untitled (After Tony Walton for Diana Ross: Live In Central Park 1983) 2024

Silk, thread, acrylic paint, epoxy, and glass tiles

Set design for Warm Up

Courtesy the artist and 47 Canal, New York

For this Warm Up season, New York City-based artist Stewart Uoo conceived a three-part modular setting for the museum terrace: a spinning mirror-tiled sculpture, hanging panels of brilliantly dyed silk, and a psychedelic DJ booth to be graced by performers in MoMA PS1’s iconic summer music series. Riffing on the alternate history of New York School painting as backgrounds for dance theater and social performance, Uoo stains the Warm Up stage in a summery palette of radical optimism. With references that include both canonical and subversive artistic interventions in the performing arts—by Cy Twombly (Bacchus, 2011) and Martin Wong (Peking on Acid, c. 1970s), among others—the main components of his outdoor installation approach the scale of architecture via painting. Suspended at the center of the installation, a custom sculpture based on a found tire flaunts inlaid mirror tiles that cast luminous track prints in their wake. Uoo’s polychromatic triptych on the DJ booth doubles as a conceptual altarpiece, encouraging crowds to dissolve into the light, haze, and heat each Friday night—and let the rhythm take over.

Kari Rittenbach: When we first spoke about this commission, you brought up several avant-garde painting collaborations with dance and theater. Tell us about some of your research and source materials for this installation.

Stewart Uoo: I was looking at sets by Robert Rauschenberg for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company and other projects at that scale, including the Wiener Staatsoper’s (Vienna State Opera) Safety Curtain series. It was interesting to see people–dancers and/or audience–in the space of color field painting, and to see its correlation to stage design. I was also looking at artists like Morris Louis and Helen Frankenthaler. I am interested in the ways that pigments soaked into canvas materially complicate figure-ground relationships, and I’ve long considered how these modernist approaches relate to my own affinity for Eastern silk painting.

KR: Would you say that your meditative practice also influenced your use of abstraction here?

SU: The title of the triptych painting installed on the DJ booth is Contemplating Non-Dualism, which is my interpretation of an idea taken from Buddhist philosophy. It refers to a way of thinking about time as vertical and spatial rather than organized on a linear, horizontal plane. It invites an expansion of–or liberation from–your own egoistic sense of individuality.

KR: An expansion of ego via decentralization, dissemination, dissolution? When you proposed the idea for the sculpture Used Sun (Mirror Eclipse), I was struck by the implication of a void at the center of the installation, rather than a regular spherical form.

SU: This artwork is an extension of some others that I’ve made; for which the inner circle of the (found) tire functions as an iconic image. It can also be read as a void. But in this case, I see it as an eclipse. There is dichotomy and simultaneity in an eclipse; whatever is illuminated is always accompanied by shadow. I thought about how a disco ball, although mirrored, actually scatters individual rays on reflection.

KR: It splinters the light.

SU: Exactly, it splinters. It also splinters your figure-ground relationship in real space, and creates a dissociative effect. But also, iconically, the disco ball represents the moon or the sun within a club or dance environment.

KR: Sort of like a locus, right?

SU: A focal point. That makes me think of other ancient rituals for which people come together to worship the sun or moon. There is still an echo of those traditions across cultures.

KR: The concentration of energy in a crowd has real power. Can you speak about your process in making these works?

SU: For the paintings on the DJ booth, I tried pouring pigment at first, but my approach became almost forensic as I developed tools to achieve different velocities. There are gestures here resulting from actions, but a lot of marks are really the product of accidents based on certain angles or the way a tool was used, or how pigment was sprayed, dripped, expelled. There are varying degrees of intuition, mishap, and authority with regard to my own agency.

It’s such a new body of work and new methodology for me–I was trying out a new relationship to control.

And I was also very conscious of palette. The color of rainbows in the 1970s and 1980s was just so different to the spectrum that has become a political standard or commercial logo today. I was concerned that the proportions of the central painting would read like a flag, which I wanted to avoid. It is interesting to bring these symbols together for this stage design, as a backdrop for figures within three-dimensional space. If flags mark borders, nationalities, and separation, there is something cool about disintegrating symbolic form in a setting where people come together to dance. I’m especially interested in reworking these symbols in relation to the rituals of performance and music, which uniquely offer a kind of coming together in shared space.

Stewart Uoo is an artist based in New York City. Uoo studied at California College of the Arts, San Francisco, and at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste-Städelschule, Frankfurt-am-Main. He works primarily in sculpture, as well as collage, installation, photography, drawing, and painting. He participated in Greater New York 2015 and has been included in exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; White Columns, New York; The Rubell Museum, Miami; Bergen Kunsthall; Künstlerhaus, Graz; Friedericianum, Kassel; Chi K11 Art Museum, Shanghai; and the 10th Gwangju Biennale, among other venues.