Las Nietas de Nonó

- Writing

mulowayi iyaye nonó and mapenzi chibale nonó find healing and liberation in creating art—and finding food—beyond the limits of traditional institutions.

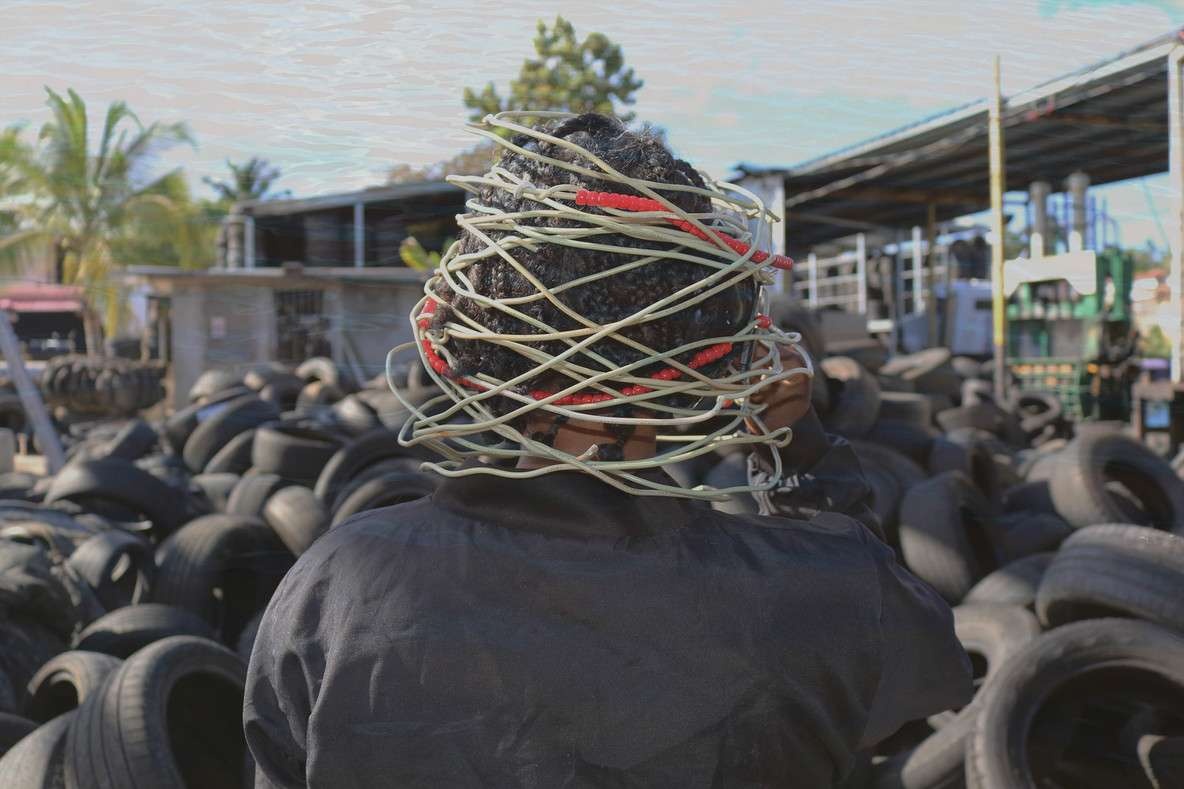

Foodtopia, después de todo territorio (Foodtopia, After Every Territory), a film by Las Nietas de Nonó, documents mulowayi iyaye nonó and mapenzi chibale nonó during the COVID-19 pandemic, when they subsisted for a period of time exclusively on hunting and gathering. The film, which screened as part of MoMA PS1’s Greater New York 2021 and was made with the museum’s support, is an example of the duo’s feminist, decolonial work, which focuses on the history of the oppression of Afro-diasporic communities in the Caribbean and the survival of their knowledge.

In this conversation, the artists discuss their work’s relationship to territory, understood in its spatial as well as historical meanings. They also provide insight into their practice and mode of working, which emphasize a self-organized approach independent from the support of institutions.

Translated from Spanish by Christopher Winks

Inés Katzenstein: Your lives and work have crossed in a very productive way. Living and working together seem part of the same experience. So I’d like you to talk about the Barrio San Antón, in Carolina, Puerto Rico, where you live, and whether you work in something like a “studio.”

mulowayi iyaye nonó: Barrio San Antón is a place with an abundance of natural resources: there are springs, fruit trees, a gully that traverses the barrio and connects to the San Juan Estuary, an infinite ancestral wisdom about curatives and the power of plants, and a large population of iguanas. I remember that when Hurricane Hugo happened, I was 10 years old and the first thing I did when the cyclone had ended was to collect all the fallen fruit. That was all we had to eat until we ate the last cedar fruit and parboiled the last breadfruit. The barrio is split by a highway that deprives us of the possibility of walking safely; add to this the problem of displacement, which is affecting people’s quality of life. Since the 1990s, the people of the barrio have been fighting for the spaces that have been affected by the different industries that have been stationed in our community. This has led to a deterioration and abandonment of spaces; it seems as if we’ll never stop fighting this. In 2017 they closed the three schools in the community and this has also touched off another avalanche of displacement.

I’m interested in working in studio and collaborative spaces. But really, I don’t think what we do can be contained in any single space or in a studio as such. We move around a lot; I’m also a community organizer. Our practice is dedicated to having conversations with people, exploring places, walking, sharing knowledge with the elders. Studio space offers us more of a limitation than a possibility. In the barrio we have a house we inherited from our paternal grandparents. The space of the house functions like a kind of archive which has part of the family history. We invite people there; several theatrical and performance pieces have been presented there. At the same time, it’s the place where we store some of the objects of our work. Now the house is in transition because we’re collaborating on organizing a community space in the school that the government closed.

Inés: Could you talk about the creation of the so-called “Patio Taller” in your grandparents’ house?

mulowayi: At that time my children were eight and 10 years old, and this was a motivation to create a meeting space, a safe space, on the property that belonged to our grandparents. We created an arts workshop space during the summers, and then we opened an artist residency and created Manual de bestiario doméstico (Manual of Domestic Bestiary). Patio Taller was the seed of the part of our practice that’s based on organizing safe spaces within the community. It was a space where art was understood as a space for healing and an exchange of knowledge: to connect to the ancestral, to make handicrafts, whatever would give us a collective feeling of being at home, like everybody cooking together in the cooking class. Patio Taller was a project that operated between 2011 and 2019; things there happened organically and spontaneously. I can say that Patio Taller was a seed because that’s how it’s viewed in my barrio. It evolved to an unimaginable extent, and we put together an ambitious and inclusive project with a community of women that we are a part of.

mapenzi chibale nonó: In Patio Taller we could imagine the possibility of La Conde, which is a project of Parceleras Afrocaribeñas, the community-based organization we founded in 2019 in collaboration with neighbors in the Barrio San Antón. La Conde was the school we, as well our father’s and neighbors, attended as children. In 2017 it was closed by the Department of Education due to the austerity policies of the Fiscal Control Board. Since then, we have channeled resources to stop the privatization of these lands and recover them for the benefit of the community using the participatory-design methodology. Now La Conde has antiracist art, health, and environment programming.

Patio Taller, in the early days of Parceleras Afrocaribeñas, was one of the places for developing the proposal for La Conde. We got together to organize, coordinate, design, imagine, make our collective check-ins, meet up with allied organizations, hold planning breakfasts, create strategies of recovery and advocacy. It was our principal base when we began developing the Project. Once La Conde was rehabilitated in 2020, we saw Patio Taller differently. Presently we’re rethinking the next stage of the space because the need, in terms of education and cultural and artistic creation, has been developing since La Conde. Now we are in a moment of reflection on what we’ve learned from this process and the opportunities it has granted not only to us as artists but to the community and our colleagues.

Inés: Manual de bestiario doméstico, your first work, had a completely non-institutional form. You made it in your home, the public was invited and received something to eat; there was a very organic relationship in terms of domesticity and community. How much of this had been worked out beforehand?

mapenzi: The idea to present this piece at home arrived like a revelation under a cedar tree during a conversation; mulowayi reminded me of this a little while ago. I’d forgotten that detail. But I’m delighted to remember it because the cedar-fruit is one of my favorites. Once it was decided that the house would be the space, the narrative came together and daily life took on a poetic presence that in turn became a dramaturgy. I never thought that the house would be the only space where I could present my art, but after that experience I was able to have a better understanding of my practice and our collaboration. It was also a way of healing the house through the ritual that was Manual del bestiario doméstico, as well as honoring with our art the legacy of our ancestors and receiving ashé.

mulowayi: Creating at home was the best possibility we had at that moment, because if we had let ourselves be duped by the modes of elitist production in Puerto Rico, we would still be searching for a way to generate income or convincing someone to give us support and opportunities.

Inés: Foodtopia, antes de todo territorio, the video presented as part of Greater New York, documents an experiment with hunting and gathering you carried out two years ago. I see it as a kind of manifesto on behalf of food autonomy. I am particularly interested in the tension in the video between radical survival and apprenticeship, life in the wild and industrialization. I understand that the project stems from a previous work that was called Manifestaciones en períodos de caza (Manifestations in Times of Hunting) and later reemerged with COVID-19. Could you comment on how you arrived at the experience of Foodtopia?

mapenzi: In 2020, with COVID-19, our agendas obviously changed, and this was a moment of deep reflection about what would happen with live arts, theater, performance. We live in an industrial area, and during lockdown our barrio fell silent. The noise of industry ceased completely. And that silence was like a revelation and invitation, an amorous rest. We discussed the idea of sustaining this action as a performance, and days after that call we started designing the basis of this exploration. We wanted to use costumes that could be used daily so that we didn’t have to think about clothes every day, and that way we freed up time and energy. Then we started defining the geographical area, and some questions emerged such as: what happens if we run out of food, do we extend our search to other areas? We were deciding this days before beginning the process. For the audiovisual piece, there wasn’t anything like a script until it was time to edit. It also became an investigation and living archive of our own surroundings, of how it had been changing, the risks and possibilities. There are spaces I didn’t know about until that moment. And there are practices I didn’t know about either, areas where people fished before that are now polluted. And that was revealed during the process.

Inés: In Foodtopia, there is a spatial ambiguity. At times it seems that you are in a forest or jungle, in a wild space, and at times you are in an abandoned urban space. Could you speak about this ambiguity and how it affected the experience of hunting and gathering?

mulowayi: There were some moments of tension, frustration, and sadness. If you spend 28 days in the same geographical area, food starts running out and possibilities continue to shrink. The relationship between physical effort and hunger, and all of your senses, start to change; you’re more present in your surroundings. As someone who observes her surroundings, which is another technology I use in my practice, I could take note of how observation can be mastered and how food can be found in places where in another context I would never have thought to find it. Your brain works differently. Collecting food is an active meditation that I developed and strengthened along with my smell and taste. Hunting is a powerful, arduous action, and through it I questioned everything that modernity, along with capitalism, has deprived us of. If we had to hunt to provide ourselves with all the meat we eat daily, there’d be no time for other tasks. And along with that, there are all the environmental implications for the livestock industry. Hunting in order to eat is an act of resistance, but it is also a skill; sometimes I wonder if, along with gathering wild plants, I would do it to sustain myself for seasons on end. I am still unsure whether my evolution would depend on this action. When I turned to hunting, it came very organically to me. Really, I thought I already knew how to do it. Certainly it’s integrated into my epigenetic information. I still have a few ethical questions about this issue.

Regarding the industrialized space of Barrio San Antón, I can tell you that there are insurmountable obstacles with respect to what one has to go through to find food, from the water affected by the auto industry to the visual and sonic impact, and the air. It wasn’t only about dealing with hunger, but also the sadness and frustration of seeing that we were living in little universes that sometimes connect and disconnect, and that I had to find a way of getting out of one or the other; sometimes, to get to the food, I had to cross a pile of tires leaking oil. I had to stay focused on this search because otherwise I could have been immobilized, stunned by the deterioration, unable to go any farther.

mapenzi: Foodtopia’s scenic shifts are ones we live through day by day in the barrio. If you enter a junkyard, suddenly you’re in an alkaline water spring which is of great value to our ancestors and which is part of our ecological culture and relationship to the environment.

“Unveiling hidden or silenced information can transform us in the direction of healing and liberation.” -mulowayi iyaye nonó

Inés: You’ve said that your work is aimed at “healing the wounds of our grandmothers, of our mothers, of women and men, of the family.” Could you talk about the curative function of your work?

mapenzi: We grew up in a culture of healing grandmothers. Our grandmother was a healer and her practice manifested in a highly theatrical ritualized form, developed from a creative space and with improvisational energy. In my childhood, traditional healing saved my life. I was a child who got sick a lot, and thanks to the signs of the cross, plant concoctions, and baths, I could get through these illnesses. These cures impressed me because they contained a fascinating scenic element, the deployment of objects, body movement, spectators giving proof of the healing, storytelling. Elements that form part of our imaginations are present in our practice—as, for example, the possibility of reaching catharsis through repetition and movement. Ritual is present in our practice, and because of this we have been able to continue the legacy of healing in correspondence with our contemporaneity.

mulowayi: Artistic, theatrical, and performative manifestations have healing power. In eco-familiar systems we can be trapped by situations that our ancestors couldn’t resolve. Unveiling hidden or silenced information can transform us in the direction of healing and liberation. I have understood my history through composing a narrative—which for some would be fiction—because a series of interpretations that make us conscious of something are made present. During the performance, events happen that move us, push us towards something extraordinary; though we cannot explain this because it lacks intellectual grounding, what I’m talking about can reach an audience that can remain open to and resonate with the work. You have to be present. My belief system includes the energizing power of spaces and of people, too. When they come into the light, silenced wounds can be seen, understood, healed. I hope to be able to talk more about these matters soon.

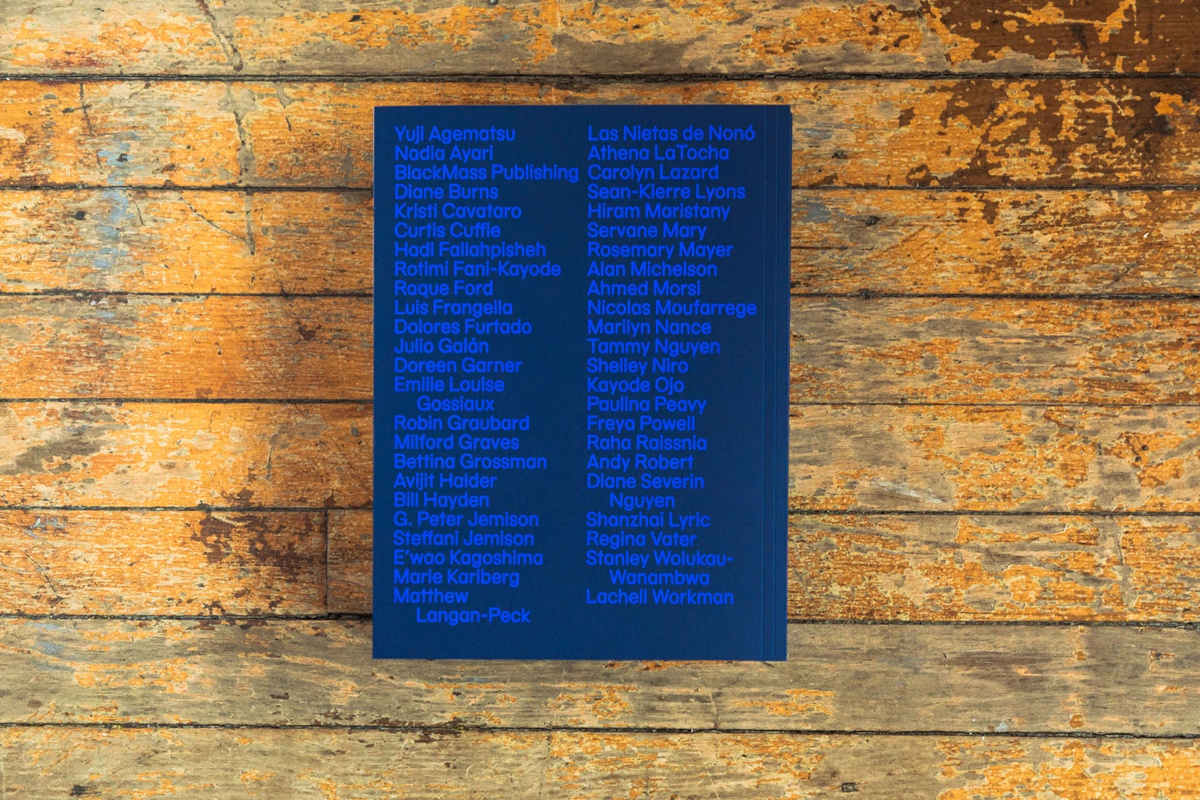

Greater New York 2021, organized by a curatorial team led by Ruba Katrib, Curator, MoMA PS1, with writer and curator Serubiri Moses, in collaboration with Kate Fowle, Director, MoMA PS1, and Inés Katzenstein, Curator of Latin American Art and Director of Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Research Institute for the Study of Art from Latin America, The Museum of Modern Art, is on view through April 18, 2022, at MoMA PS1. Foodtopia, después de todo territorio screened continuously at MoMA PS1 from April 4–18, 2022.

Director, Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Research Institute for the Study of Art from Latin America, and Curator of Latin American Art