Artists Make New York

- Video

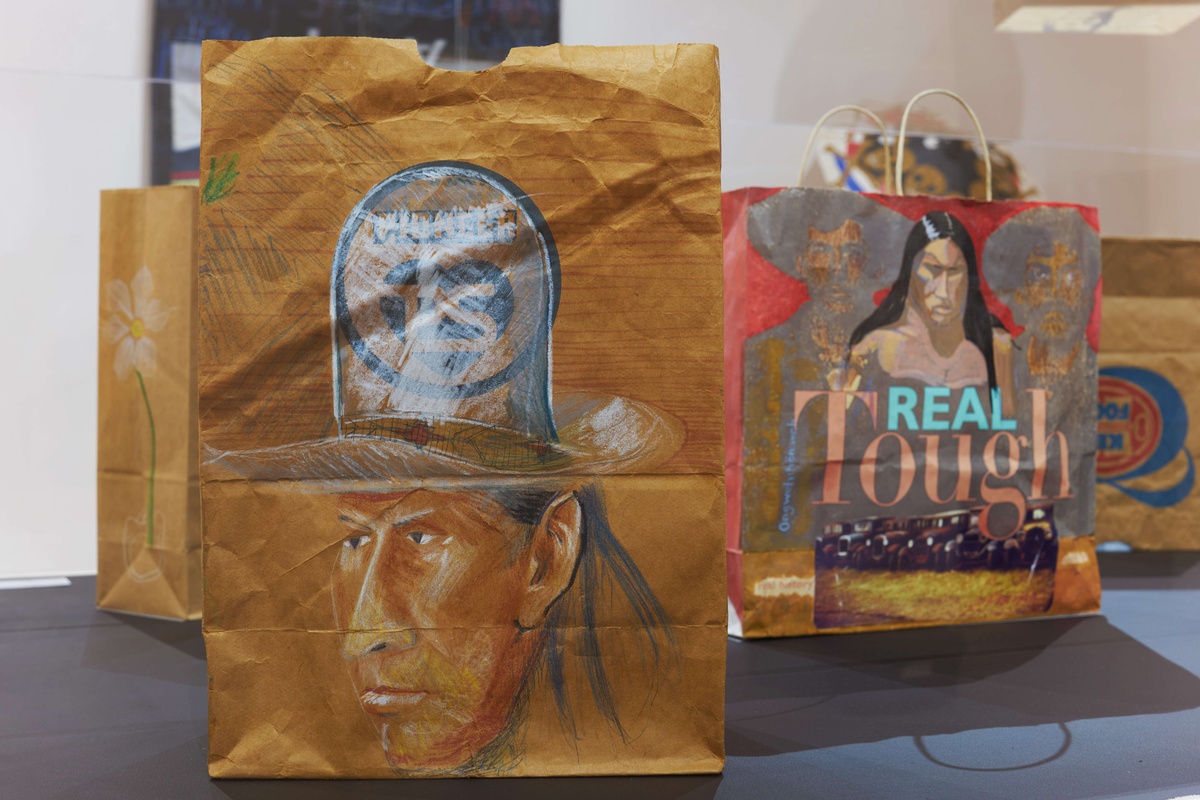

G. Peter Jemison. Party Bag. 1982.

Watch and read an interview with artist G. Peter Jemison, as he discusses some of his work in the MoMA PS1 exhibition Greater New York 2021.

Jody Graf, G. Peter Jemison, Nora Rodriguez

Mar 30, 2022

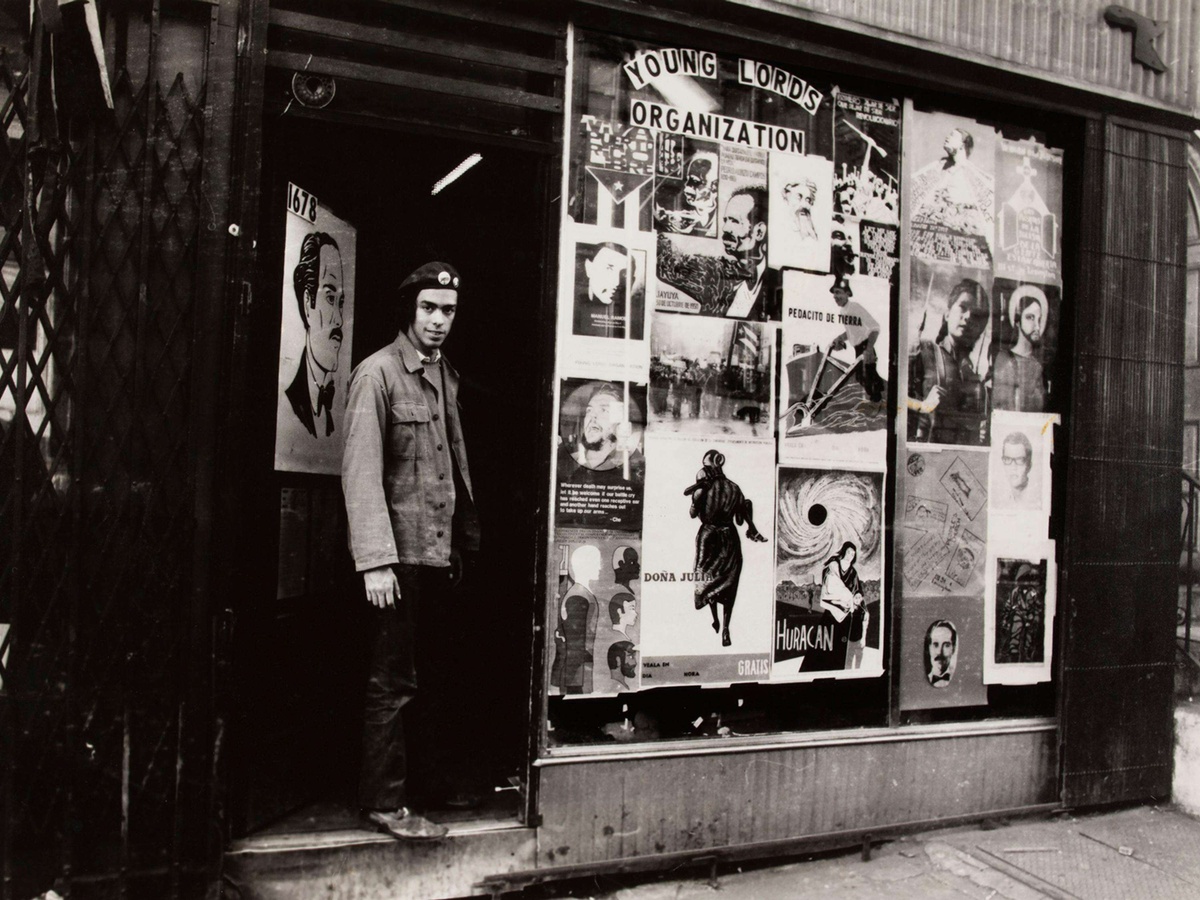

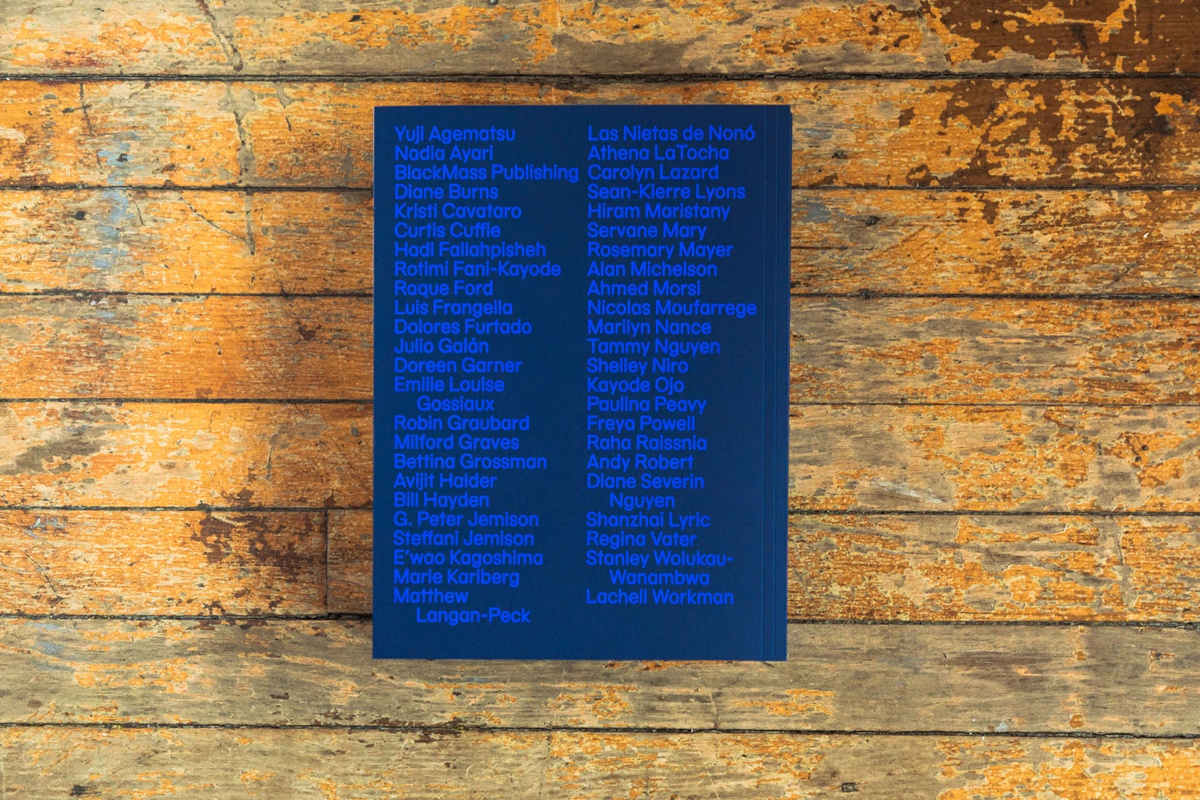

G. Peter Jemison—an artist, curator, historian, and educator—is a foundational figure in the art history of New York City, and especially its communities of Native artists. A member of the Heron Clan of the Seneca Nation, Jemison first moved to New York in the late 1960s and served as the inaugural curator of the American Indian Community House Gallery from 1978 to 1985, where he was instrumental in fostering a vibrant scene of contemporary Native art. At the same time, he was a practicing artist himself, creating works ranging from drawings on paper bags to collages and sculptures. A selection of these, dating from the 1970s to present day, are featured in Greater New York 2021, on view through April 18, 2022, at MoMA PS1.

Jemison’s artworks merge the texture of everyday experience and the long sweep of history: through stories of family and friends, we also learn those of the Haudenosaunee confederacy; the history of the treaties (made and broken by the US government) that lie behind current borders; and key events in the American Indian Movement, such as the occupation of Wounded Knee. Jemison’s works, in his words, “fill in the blanks that have been missing.” In doing so, they raise questions around how the lessons of history can remain present, and the uneven responsibility placed on certain communities to combat the erasure of their past. In addition to embedding these histories in his artworks, Jemison is also the site manager of the Ganondagan State Historic Site in Victor, New York. –Jody Graf, Assistant Curator, MoMA PS1

The following is a transcript and video of Jemison’s reflections on key works exhibited in Greater New York, as told to MoMA PS1’s Nora Rodriguez.

In Our Language. 2020

This piece is called In Our Language. It features the names of all of the people that appear in the photo collage: my father, mother, grandmother, sons, sister. I’ve identified them in the Onondowagah language by writing out their names using a standard linguistic method of accenting these words. A portion of text means “this is the creek or the river that we call smelly bank.” There’s a part of the bank that has kind of got sulfur in it. It also shows my father, who is deceased, when he was fishing at the river. And my mother, Margaret, when she was much younger, around the time that she and my father met.

We, who are Seneca Onóndowahgah, belong to one of eight clans. There’s four on the bird side and four on the animal side. My mother was from the Heron Clan on the bird side of our clan system. Therefore, I’m a Heron. My father, on the other hand, was from the Wolf Clan on the animal side, which I also identify here. I also show my father’s father holding him. So each text is identifying members of my family, or where they are. This says, Dó:sówe:ono. This is where my father was living. He was living in Buffalo, but we call Buffalo, “Dó:sówe:ono.” Dó:sówe:ono means he was there in Buffalo at the time that this photograph was taken of him. My father and my mother lived there for a while. I wanted to use the language, and I wanted to talk about my relationship to each of the people in the photos. I inherited some shoe boxes full of family photos. Some of them are tiny, so I took those, enlarged them, and then worked out a photo collage with them on a big black wall. Then I photographed it again on my cell phone, sent that to my printer, and then had it printed on a canvas. The piece is mostly about searching through those shoe boxes to figure out who all these people are that I have photos of that I inherited from my parents.

You might notice that the work is laid out as a cross. When I was young, my father was a member of a church. The church was something that figured in our lives, in our social life, and so forth. I stepped away from that particular religion, but the church relationship to the family has framed some of my childhood, and my father remained for his whole life.

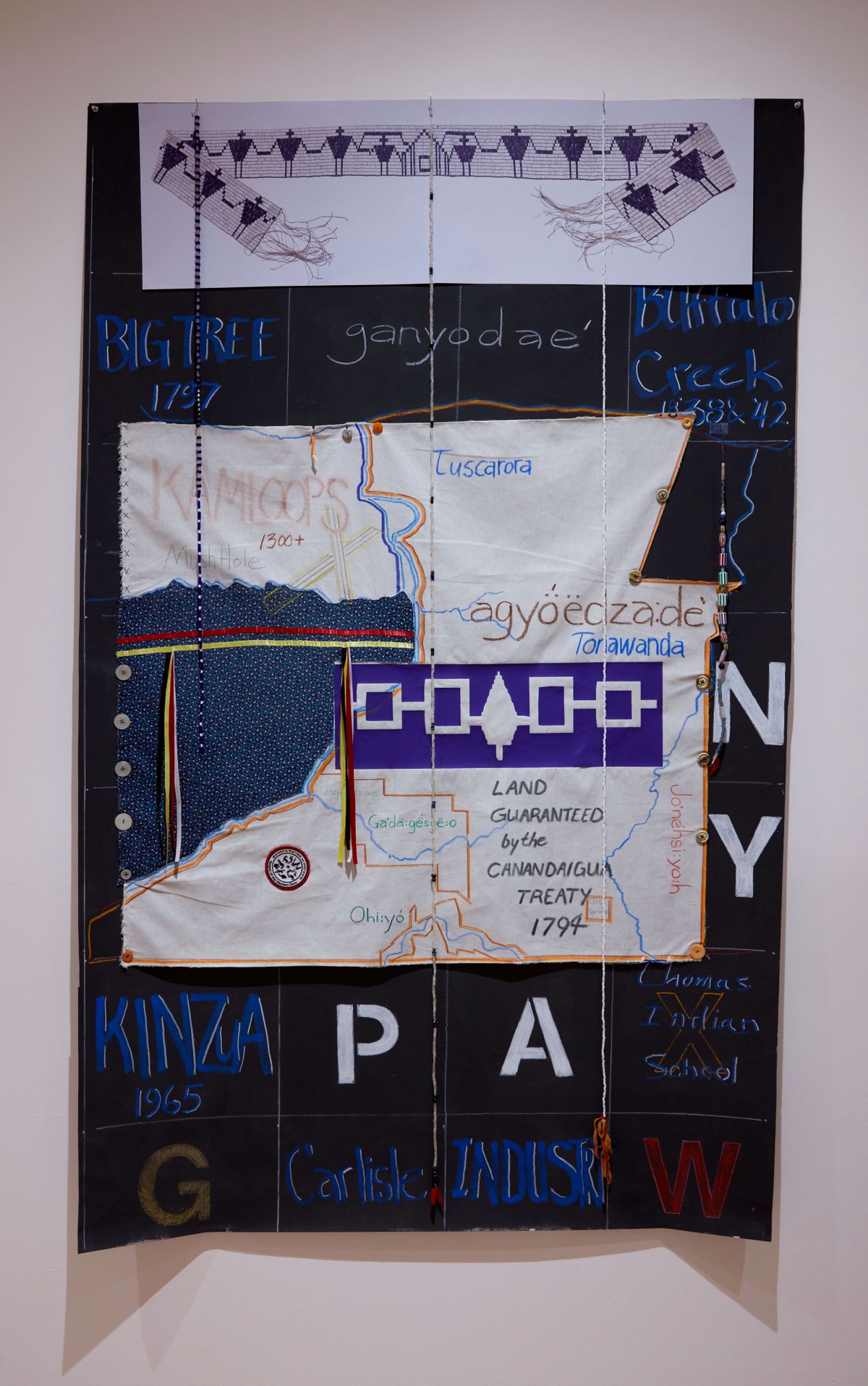

Canandaigua Treaty 1794 Land Guaranteed. 2021

This piece was produced specifically for Greater New York and I worked on it for a bit more than a year. It relates to land guaranteed by the Canandaigua Treaty of 1794, in which the nascent United States government acknowledged the sovereignty of the Haudenosaunee—a confederacy of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora people, whose name means “our people built an extended house”—in what is now known as upstate New York. The area that I have outlined in orange is on what is called “treaty cloth.” This is cloth that the United States ships to us annually as one of the terms of the Canandaigua Treaty, which was that they supply us with cloth. Originally it was a calico, like the piece of cloth with which I’ve outlined Lake Erie in this work. Eventually it became a very inexpensive muslin, which we receive today. I remember going with my grandmother to pick up our treaty cloth. I was about five at the time, holding her hand and waiting for our treaty cloth. At the time people referred to it as “annuity cloth” because it came every year. We being children, we couldn’t pronounce annuity, so we called it “nudy goods”—we were waiting for “nudy goods.” All we knew was that we’d get this cloth—but I didn’t know anything about its origin or why we were getting it until years later, as an adult, when I became very familiar with the Canandaigua Treaty and also became the chairman of the committee that commemorates the treaty.

Every once in a while, I create a piece using the treaty cloth itself, because it’s a reminder that part of the agreement that the United States made with us is to continue supplying this, even though they only set aside $4,500 annually to be able to supply us with this treaty cloth. But we’ve said, “We don’t care if the cloth gets down to the size of a postage stamp.” So long as the United States has to keep supplying this, it’s a reminder to them of the agreement they made in 1794 when George Washington was president and when the Senate ratified this treaty called the Canandaigua Treaty, or sometimes referred to as the Pickering Treaty, because it was negotiated by Timothy Pickering. What that treaty says is that essentially all of Western New York, from the Genesee River all the way to Pennsylvania, around the Southern shore of Lake Ontario, the Niagara river, the Southern shore of Lake Erie, and then back again to the Genesee River—all of this land was guaranteed to the Seneca Nation. That would’ve included the city of Buffalo, portions of the city of Rochester, towns such as Jamestown, Salamanca, Silver Creek, Dunkirk. We could go on and on naming small towns that are all within this area, including Niagara Falls. They guaranteed that to the Seneca Nation by the terms of this treaty. Do we own all this land today? No, we don’t own all this land today.

There are a number of symbols included in the piece: this [collaged image of wampum belt] is a symbol for our Confederacy of Five Nations, sometimes referred to as the Hayenwatha Belt or the Hiawatha Belt. So if we begin on the west of the area, it’s Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk. These five nations were united by the message of peace, power, and righteousness into a Confederacy for about 1,000 years. This [points to belt] is the wampum belt that we keep to remind us that we are united by the message of peace. Peace is represented in white. Purple represents the time of conflict when we were constantly fighting with each other, until this message of peace came, which was intended to get us to stop killing one another and resolve our differences by using the power of the good mind.

The belt at the top is the belt that was presented by George Washington to our people as an emblem or as the symbol of the Canandaigua Treaty. It shows 13 large figures, which are the 13 original states, united with the two in the center. One interpretation I have is that on the left, it’s the Mohawk nation and on the right it’s the Seneca nation. The two smaller figures are linked arm and arm with one another in a message of peace. There is a symbol for our house, the bark longhouse, and a symbol for something like the White House in the very center of that. There’s this idea that we can travel in peace into this territory. The door is open so long as we travel in the message of peace. That’s one interpretation of the Canandaigua Treaty belt. The belt was made by two Oneida women. The shell bead that is used in the belt comes from the Atlantic Ocean. It’s North Atlantic shell that is taken over to places like the Pequot in what today is called Connecticut, where they took the shell and formed it into beads. The beads were traded to us and we fashioned them into wampum belts. Not a belt to hold your pants up, but a belt to record an important idea. Anthropologists call it a mnemonic device: when you hold it, you can both see and feel the message that was woven into it.

Party Bag. 1982

This work addresses a history involving the American Indian Movement, or AIM. Many people don’t know much about AIM. If someone has done any reading at all, they might know about the occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973, when AIM took over a town in South Dakota. The story of this bag is really about the person whose portrait appears on it: a man whose name was Bobby Onco. Bobby Onco was a friend of mine, and he was a member of the Kiowa nation. He was a veteran of Vietnam, but he was also one of the men who occupied Wounded Knee. Not too many years after he came home from Vietnam, just two or three years afterward, there was a rash of killings in places like South Dakota and North Dakota of Native people. There didn’t seem to be any justice. There didn’t seem to be any prosecutions for the fact that these men and women had been killed. So Bobby and others really felt that they had to bring attention to the failure of the government to prosecute these murders. That was part of what led to the occupation of Wounded Knee.

Being a veteran of Vietnam, Bobby had some really horrifying stories about his experiences, including the fact that at one point he was captured by the Viet Cong and was being transported in what they called a tiger cage, made out of bamboo. He managed to escape, but he, really—well, he had to kill his two captors to get away, and then he had to crawl through the jungle till he got to American lines where he was safe. When he was in Wounded Knee, he was one of the few people who could use an AK-47. He could take it apart, assemble it, and fire it. Wounded Knee became surrounded by militia, by local law enforcement from different areas of the state of South Dakota, and the US government also sent in armed forces. They were shooting continuously into Wounded Knee. As a result, the people that were in Wounded Knee felt the need to fire back in order to protect themselves and to make it clear that they couldn’t simply be attacked and taken. They were trying to negotiate a peaceful settlement to this ongoing conflict. Bobby was named a warrior by the women that were more or less in charge of the occupation. These were Lakota women. They considered him to really be a warrior. This is a role that our men played in all of our different communities: a role of protector, a role of defender, a role of a person who is trained to endure hardship and to travel great distances when necessary to maintain the relationship that we had to the land. This is a tradition that goes way, way back, and this is a tradition that Bobby came out of. I met Bobby in around 1976, and when I knew him, he had come out of Vietnam and Wounded Knee, and he had some really difficult encounters with the FBI. The FBI continued to dog him and follow him pretty much the rest of his life because of the training he had received in Vietnam, and because of the fact that he was at Wounded Knee in South Dakota.

This bag has all of that history incorporated into it, even though there were times when he and I sat around and had a few beers and talked about things unrelated to any of that. He was also a very qualified electrician. When I moved the American Indian Community House Gallery from Midtown Manhattan to Soho, Bobby wired the entire lighting system on the inside of the gallery space by himself. The histories in my art are ones that I know firsthand. I lived it. And so it becomes the subject of my art. And the main thing I’m always concerned about is that my work has an authenticity. It’s not something I’m grabbing out of the air and I don’t know anything about. That’s not the way I work. I work from the basis of this is something I know, something I’m still trying to understand, and that it takes a lifetime to fully understand.